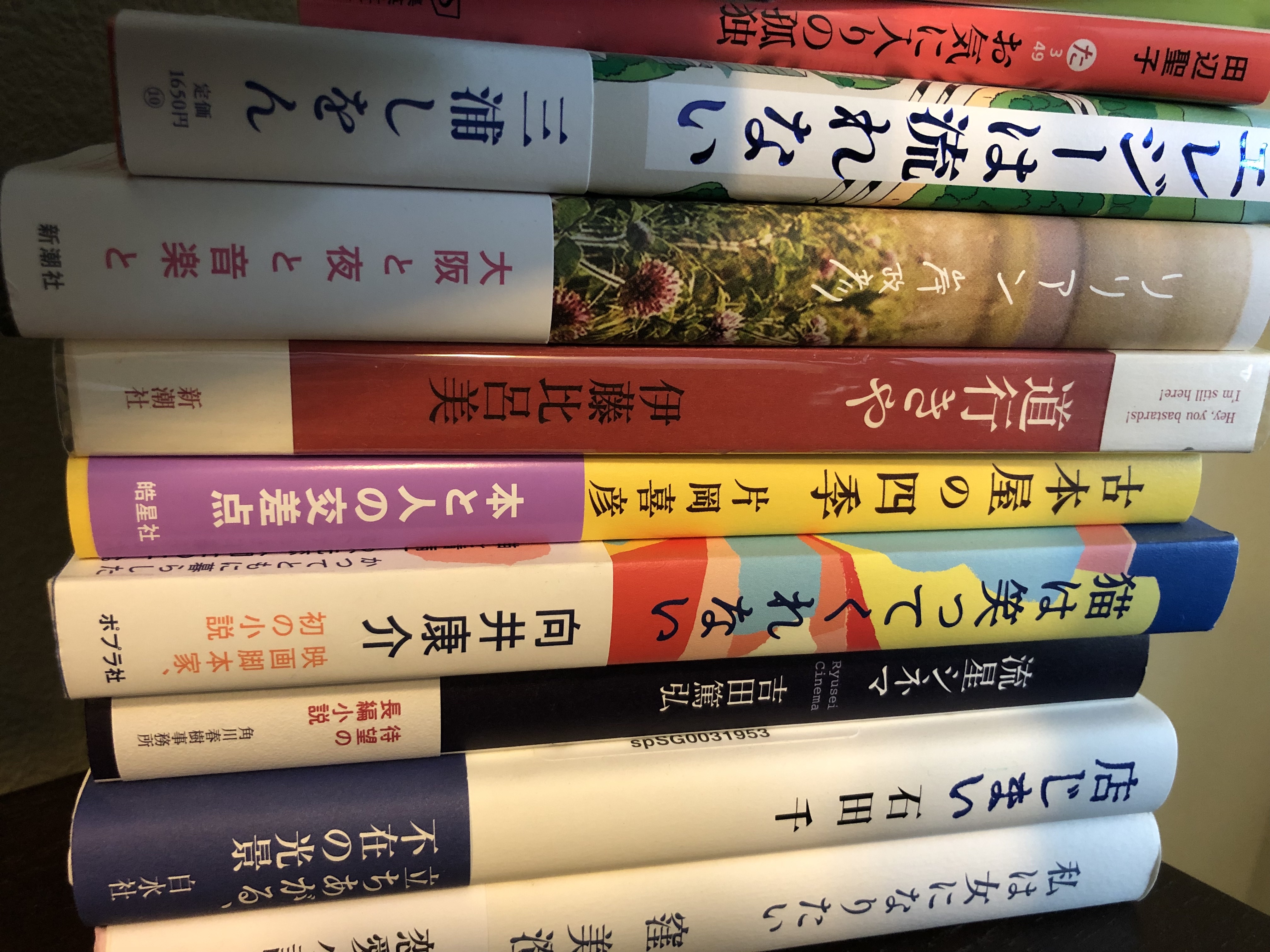

1R1分34秒、町屋良平、新潮社、2019

One Round, One Minute, 34 Seconds, by Ryohei Machiya; published by Shinchosha in 2019

The brief description of this book found on the publisher’s website gives the impression that this is a story about an athlete overcoming the odds and making a comeback. That is not quite what this novel delivers. Both the writing style and the narrator himself give us an uncomfortable reading experience that mimics the rhythm of boxing and the discomfort our boxer experiences in his training.

When the book begins, our boxer has lost a match and in short order also loses his trainer and his part-time job in a pachinko parlor. We are never given his name, and in fact the boxer’s lack of a name seems appropriate because his identity is so shaky. In the first half of the novel, he can no longer even believe in his body, he is tired of his physical and mental weakness, and no longer knows whether he even wants to fight anymore. In the second half, he has committed to another fight but his weight-cutting regime makes him nearly delirious and the reader cannot always distinguish between mirage and reality.

The new trainer that his gym assigns him, Umekichi, is the only character in this novel whose name we are given. A boxer himself, he hasn’t ever trained another boxer, but our boxer decides to try his unconventional methods. This is no heartwarming story of trust developing between two people—our boxer merely decides to try on “trust” for size and see if this “system” or “game” will work for him. In between training, our boxer goes on outings to museums and movies with his (only) friend, spends time with his “sex friend” (whom he kicks out without remorse when his training regime becomes too stringent for such diversions), and obsessively researches his next opponent. He even imagines hanging out with the opponent, watching a couple having sex in the bushes at a park or reading porn at the convenient store together. Yes, our narrator is a little strange…

Machiya makes this reading experience even more disjointed by writing words that would typically be written in kanji in hiragana instead, creating a staccato rhythm. He also occasionally threw in some difficult kanji that are no longer used, or used kanji for words not typically written in kanji (like 軟派instead of ナンパ). He almost seemed to be mirroring the boxer’s mental breakdown as he cuts weight.

There was one particularly striking scene that has stuck with me. His friend takes him on a “trip” when his next fight is scheduled, which is a tradition of theirs. They take a late train to the last stop, eat lots of meat at a Denny’s restaurant, and go down to the river, where his friend uses his iPhone to film him shadow boxing. His friend becomes almost delirious with excitement, and runs along the beach filming the rising sun and the boxer until he falls and nearly loses his iPhone. The phone is undamaged, but he has a bad cut on his hand. On the train on the way home, the boxer drips disinfectant onto his friend’s injured hand as he sleeps. He lays a towel underneath his friend’s hand (the only sign of gentleness we ever see from him in the novel). Then he pours the whole bottle of disinfectant on his friend’s hand in an effort to clean it, but forgets his intention as becomes entranced by the way the disinfectant traces tiny diamond shapes on his skin and reveals the cut, bleeding in spurts almost as if breathing. This oddly soothes the boxer so that he is finally able to fall asleep. For me, this summed up the boxer’s intensity and odd perspective on things.

The title refers to the last sentence of this book, when rigorous training and weight-cutting is robbing him of his sense of self:

“I’ll win; I’ll definitely win.” …Every 30 seconds he’d lose this resolve and then repeat it again. He had to go through two more of these nights, just for an unexpectedly easy win by TKO in one round, one minute and 34 seconds three days from now.

This expresses the frustration of putting so much time and work into preparing for a fight that can be decided in as little time as one minute and 34 seconds. Machiya marshals both writing style and content to show us that boxing has such a tight hold on this boxer that he cannot give up on this harsh sport.

Recent Comments