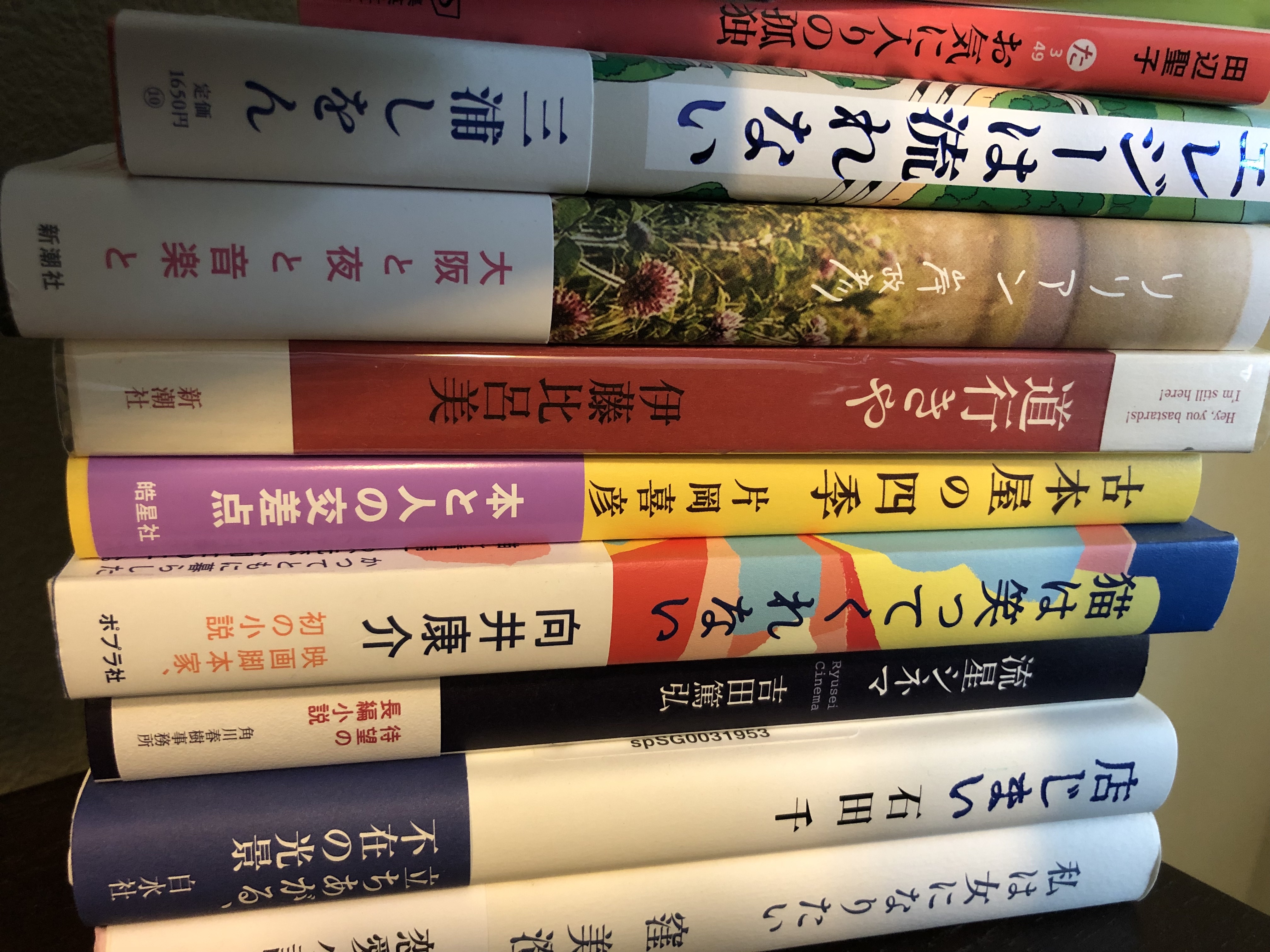

ニムロッド、上田岳大、講談社、2019

ニムロッド、上田岳大、講談社、2019

Nimrod, by Takehiro Ueda, Kodansha, 2019

In Nimrod, which won the 160th Akutagawa Award (shared with Ryohei Machida for his 1R1分34秒), Takehiro Ueda experiments with several different narrative techniques to look at bitcoin and some of the questions that this cryptocurrency raises. Although he doesn’t answer all these questions, he sure seems to have fun trying, and as an executive at an IT security company and an award-winning novelist, he is better placed than most to do so.

Ueda names his hero after the bitcoin founder Satoshi Nakamoto, although his Satoshi works at a mid-sized IT company with responsibilities that are neither particularly taxing nor interesting. He is a very ordinary, upright man, perhaps lacking in curiosity but always kind. He runs when his girlfriend summons him, carries out his boss’s capricious instructions, and is unquestioningly loyal to his friend Nimrod. When the book begins, he has just been promoted to head a new department (in which he will be the only employee) that will mine bitcoin, and he learns the software in much the same way one would follow a recipe for a stodgy casserole. The questioning and philosophizing in this novel are mostly delegated to his girlfriend Noriko and his friend Nimrod, a former colleague who now works in another city.

In interviews (such as on Session 22), Ueda has said he became interested in bitcoin when its price soared to a record high in late 2017, and was even more intrigued to learn that the person who developed bitcoin goes under the name Satoshi Nakamoto, and yet no one knew who he was (or even whether he was actually Japanese). Ueda was also fascinated by the life of Shoichi Ota, who came up with the idea for the Ohka (cherry blossom), a manned flying bomb that pilots used in WWII in what were essentially suicide missions. Ueda saw parallels between the elusive Satoshi Nakamoto and Shoichi Ota, who took a plane out three days after the war ended and disappeared, but was later discovered living under another name. Ueda began writing Nimrod to explore these two motifs.

France’s C.450 Coléoptère; Source: Wikipedia

The novel consists of Satoshi’s narration, interspersed with emails from Nimrod, who used to work with Satoshi at the same company but was transferred to a branch in his hometown when he became seriously depressed (at least partly because he failed to win new writer awards three times in a row). Now he sends Satoshi long emails that describe “useless airplanes”—experimental airplanes that were designed and built but never worked. Nimrod is fascinated by these planes because of the leap of faith in the face of logic (or science, for that matter) that they represent. In addition to the Ohka, Nimrod writes about the Convair NB-36H, a nuclear-powered plane that had a section for the crew that was lined with lead and rubber to protect them from radiation, the SNECMA C.450 Coléoptère, a French aircraft that was designed to take off and land vertically so that it needed no runway, and the British Aerospace Nimrod AEW3, a hugely expensive attempt to develop a plane equipped with a radar system to provide early warning for the UK. Nimrod feels that these planes, even if they were expensive mistakes, are still a symbol of a cheeky insouciance that allowed people to flout logic and invent something new. This is often how human advances are achieved, but the Ohka was different since it was in the service of death. After relating its history, Nimrod seems to tire of these planes and begins sending Satoshi excerpts from his novel, about a King Nimrod living in a distant future who collects these useless airplanes.

Ueda depicts a normal person living in a world in which bitcoin—something that is not based on anything tangible—can reach incredible prices. This is not a dark, dystopian vision—Satoshi’s girlfriend loves to hear stories about Nimrod because they reassure her that the world is essentially gentle if a person so obviously different has a secure place in the world. When I finished Nimrod, I didn’t feel like I knew what Ueda was trying to say, and in fact I have no idea what the end meant. I even questioned why it had won the Akutagawa Prize. But I think the judges are trying to recognize works that try something a little different and maybe even start conversations, and I think Ueda did that with a novel that bumps technology down to the mundane everyday level with an ordinary salaryman working for a completely unremarkable tech company, while still asking how we grapple with our dependence on something whose inner workings we don’t understand. And while the book didn’t offer any coherent “message,” Ueda surely gave his novel and a key character the name “Nimrod” for a reason. Reading this, it’s impossible to forget that it was Nimrod that, according to Jewish and Christian tradition, led the work to build the Tower of Babel in a desire to reach heaven, and this hubris resulted in the end of linguistic unity and the start of our inability to understand one another.

The Tower of Babel, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Recent Comments