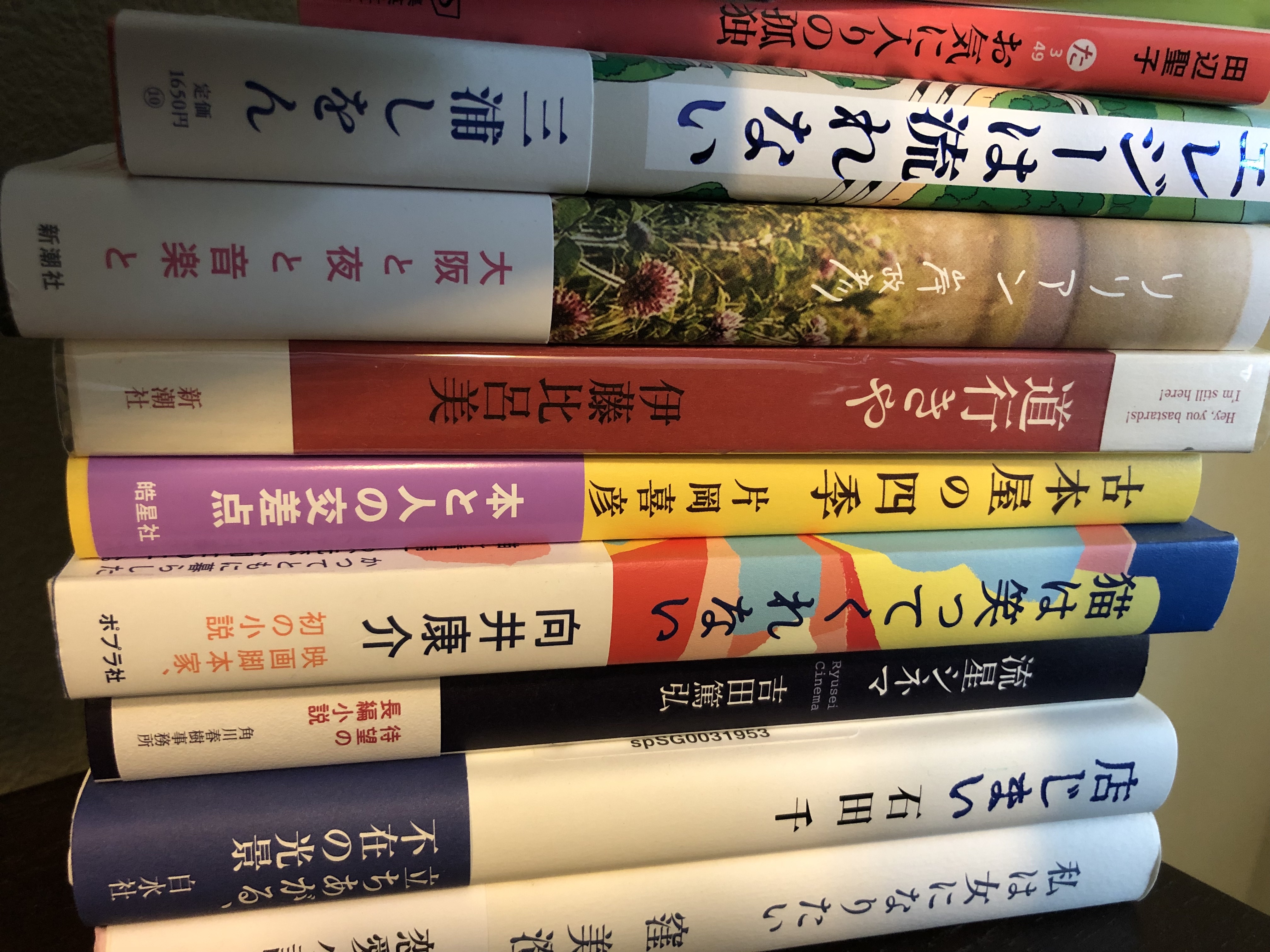

I love reading; it’s my favorite thing to do. I know I’m not alone in this—luckily, there is a whole tribe of us out there, people who understand the complicated calculus our brains go through to figure out what book(s) to bring along while we brush our teeth and wash our faces and take baths (it must be light enough to hold but also lie flat). And surely I’m not the only who has hidden from my children, hoping no one will ask for dinner until I finish my book (that book, by the way, was 「ナミヤ雑貨店の奇蹟」by 東野圭吾, an otherwise forgettable novel but a great example of addictive plot structures). One of my husband’s many lovely qualities is that he never raises an eyebrow when more books appear in the house (although once—only once—he gently suggested that I adopt a “just-in-time” inventory system for books, and was alarmed to find that the linen closets no longer shelve linens). But although I read as much and as widely as I can, in two languages, it is still rare to find a book that truly sparks something—a flicker of recognition, a sense that I have found a perspective or way of looking at the world that slots right into an empty spot in my brain.

I found this in a novel called 『これはただの夏』[Just an Ordinary Summer] by 燃え殻 (Moegara), which I read, appropriately, on a hot summer day in Portland, just when things were (briefly) opening up. I started it in a coffee shop and finished it in a hotel bar, started it all over again, and then ordered everything he had previously published. When it comes down to it, his appeal for me lies in the way he makes sense of the world and finds solace in all of its messiness and sadness. In the introduction to his second book of essays, 『夢に迷って、タクシーを呼んだ』[Got Lost in a Dream, Called a Taxi], Moegara describes a walk he took one day to try and find inspiration ahead of an essay deadline. He found it in a pig’s foot inexplicably lying in the middle of the street in a neighborhood of love hotels. This account perfectly illustrates the appeal of Moegara’s writing: he is endlessly curious about the grotesque and the mundane, and finds interest and even a kind of romance in both.

I found this in a novel called 『これはただの夏』[Just an Ordinary Summer] by 燃え殻 (Moegara), which I read, appropriately, on a hot summer day in Portland, just when things were (briefly) opening up. I started it in a coffee shop and finished it in a hotel bar, started it all over again, and then ordered everything he had previously published. When it comes down to it, his appeal for me lies in the way he makes sense of the world and finds solace in all of its messiness and sadness. In the introduction to his second book of essays, 『夢に迷って、タクシーを呼んだ』[Got Lost in a Dream, Called a Taxi], Moegara describes a walk he took one day to try and find inspiration ahead of an essay deadline. He found it in a pig’s foot inexplicably lying in the middle of the street in a neighborhood of love hotels. This account perfectly illustrates the appeal of Moegara’s writing: he is endlessly curious about the grotesque and the mundane, and finds interest and even a kind of romance in both.

Moegara; Source: Softbank News

Moegara took a circuitous path to the writing profession. A fairly hopeless student, he went to a third-rate vocational school and then worked in an éclair factory and as cleaning staff at a love hotel, among other jobs, before finding permanent work in a TV production company. He began writing on Twitter under the name “Moegara” (which means “embers” and comes from a song of the same name by Yasuyuki Morigome) and attracted attention for the lyricism and self-deprecating humor of his tweets. As Moegara tells it, Kazuhiro Ozawa, part of the comedy duo Speed Wagon, sent him a message via Twitter and asked if he wanted to meet up at a creperie (I love that detail) to talk. They ended up back at Ozawa’s house, where they began talking books and realized they both liked the author Takehiro Higuchi. Ozawa offered to throw a birthday party for Moegara (this is just hours after they’ve met for the first time), and at this party, Ozawa introduces him to Higuchi as a surprise. Apparently their conversation about novels and pro wrestling was enough to convince Higuchi that Moegara should start writing. So when they get together for drinks later, Higuchi calls his editor (at 2am) to arrange for Moegara to begin writing a weekly serial on cakes (you can still read Moegara’s writing here, including the first chapter of his first novel).

The poster for the film version of 『ボクたちはみんな大人になれなかった』, which can be found on Netflix as “We Couldn’t Become Adults.”

This became the novel『ボクたちはみんな大人になれなかった』[We Never Grew Up], published in 2017 when Moegara was 43. From the vantage point of middle age, the narrator recalls the period in his early 20s when he met someone he came to love more than himself and began working for a scruffy start-up TV production company. Moegara has been dubbed “the Reiwa era’s Murakami,” and while I think this reflects the media’s need to cubbyhole every newly popular author, Norwegian Woods and 『ボクたちはみんな大人になれなかった』are similar in that the main character in both have lost someone, and must live with this pain and regret. This novel became a major bestseller (it sold out so quickly that bookshops would issue announcements via Twitter whenever they managed to get new stock in and asked that everyone restrict themselves to a single copy). It was also made into a movie, released in theaters and on Netflix worldwide in November 2021 (I enjoyed it, especially as a chance to see Tokyo in the late 1990s again, but the movie adds a lot that is not in the book and to me, the main character has none of the bumbling charm that he has in the novel).

Moegara mined his own past for this first novel, which is largely autobiographical. In his second,『これはただの夏』[Just an Ordinary Summer], published in July 2021, he picks up with the same narrator several years on, still struggling to perform the role of a “normal” adult, and gives him the chance to experience family life for a brief interlude. Through a strange series of events, Akiyoshi is made responsible for Akina, a little girl in his apartment building who is arguably more mature than he is. Yuka, a woman he met at a wedding who turns out to be a sex worker, rounds out their pseudo-family, and Ozeki, a TV director Akiyoshi works with who has just been diagnosed with stage 4 cancer, provides running commentary from his hospital bed. Akiyoshi has always felt that he is merely (clumsily) acting the role of an adult but, if only to show Akina that adults haven’t made a complete hash of it, Akiyoshi and Yuka begin to take the game a little more seriously.

A poem in a picture; Source: 松本慎一

Beyond these four main characters, Moegara packs a large cast of characters into the 200 pages of this novel, none of whom seem to have traditional jobs and at least three of whom work in the shadier side of the entertainment business. In that sense, Moegara can be read as a successor to Nagai Kafu, who filled his novels with prostitutes, geisha, and cabaret dancers, but Moegara describes the hostesses and sex workers who appear in both of his novels in a matter-of-fact, straightforward way, with no prurient fascination to cloud his depictions. He uses this cast of people living outside of traditional social units to bring into sharper focus his themes of family, death and what it means to be an adult. Some of these characters are part of Akiyoshi’s everyday life, and some surface from his memories, which are as real to him as his physical environment: single mothers, supporting their children by working at snack bars; the outcasts from Saitama, South Korea and Thailand who have washed up on an island to work as hostesses; an elementary school classmate who became a hikikomori (shut-in). Akiyoshi is also tortured by the memory of finding the bodies of a co-worker who died of overwork and a client who killed himself. In that sense, this novel is about two kinds of partings: the absolute divergence brought about by death, and separations that feel as final as a death, with the end of summer marking these partings.

And yet for some reason, this novel is quite funny, with flavors of humor as varied as the characters. Akiyoshi’s phone conversations with his mother, who just wants him to lead a “normal” life, are instantly recognizable as the unintentionally ridiculous monologue of any self-righteous parent. Yuka and Akina are merciless in mocking Akiyoshi, and Ozeki’s bluster adds gusts of energy, even though he is dying. A pair of comedians repeatedly pop up throughout the novel in videos, the radio and TV, effectively playing the role of Shakespeare’s court jesters by propelling the plot along, setting the mood, and revealing secrets within their riffs.

『これはただの夏』is set in summer 2018, two years before the Olympics were scheduled to begin in Tokyo, and Moegara weaves the Olympics into the background, overheard and overseen in the form of radio announcements, comedy routines and posters. The reader also knows that, though Moegara may stress that this is an “ordinary” summer, it is one of the last such summers before the pandemic quashed our idea of “ordinary.” The notion of brevity is implicit in summer; in music and literature, summer is a period of release from quotidian constraints, but always with the understanding that it will end. When the novel begins, we know the ending already, which makes the short-lived ties Akiyoshi forms bitter-sweet.

If you’d like a taste of Moegara’s essays, which deserve a post of their own, you can listen to an actress read several here. Moegara also has a podcast with the adult movie director Hitoshi Nimura (even if you don’t understand Japanese very well, their voices are so soothing that it is like a lullaby).

It sounds like a wonderful book; filled with character.

Yes, the best characters! I’m hoping that Moegara’s Netflix film will get him more attention so that his novels and essays can be translated.

Yes!