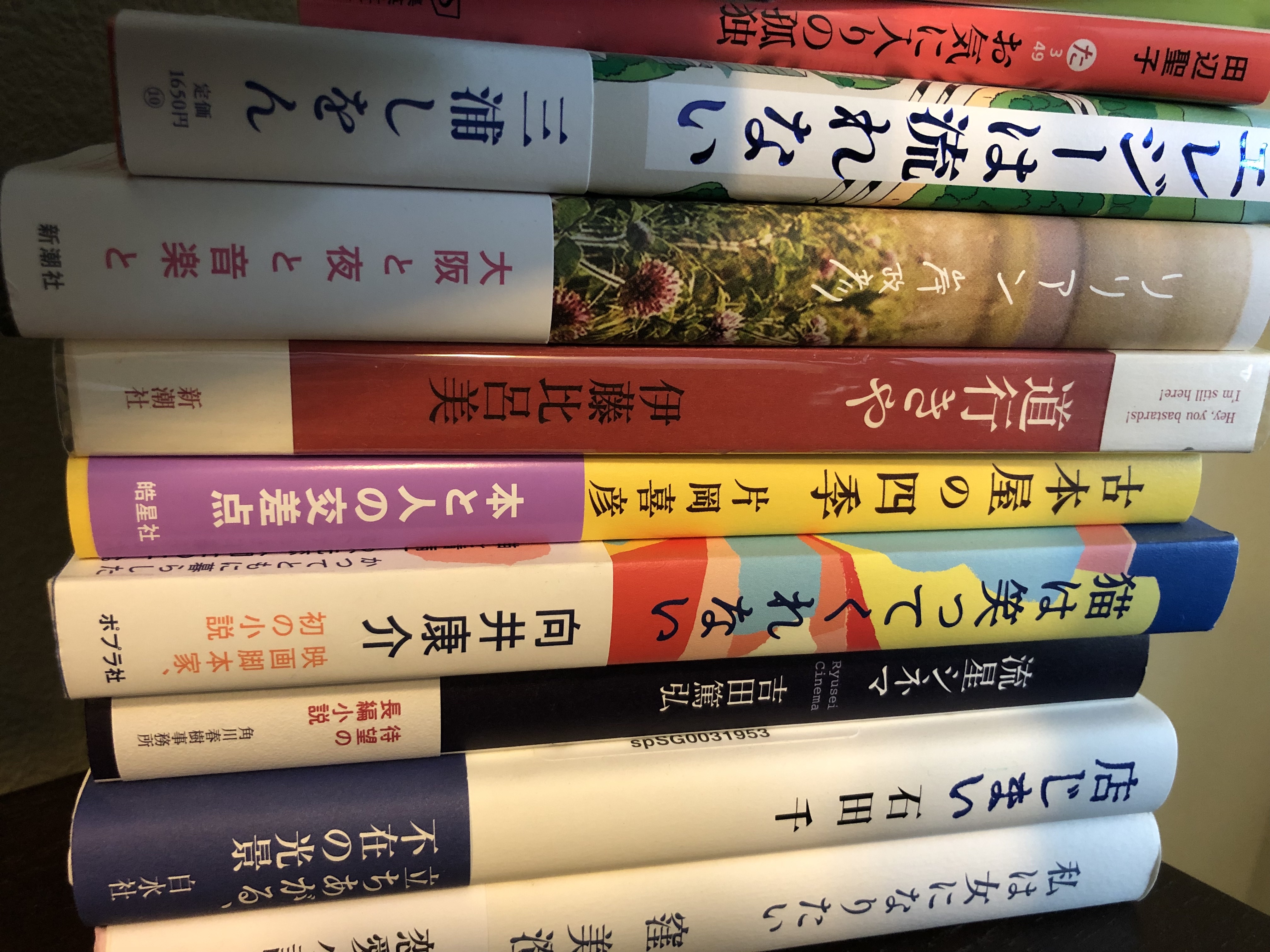

The end of the Christmas and New Years holidays don’t seem such a letdown because I have both the announcement of the Naoki and Akutagawa Awards and the nominees for the Japanese Booksellers Award to look forward to. This year, I woke up to the news of the Naoki and Akutagawa awards and waited up for the Booksellers Award announcement, with the US presidential inauguration sandwiched in between, so it was a banner day. As one bookseller said, bookstore employees are supposed to nominate books that are not necessarily selling well but deserve more readers. This year, I would happily read just about every book on this list.

『犬がいた季節』伊吹有喜

『犬がいた季節』伊吹有喜

Seasons with a Dog, by Yuki Ibuki

In late summer 1988, a puppy finds his way into a high school, and for the next 12 years, students take care of the dog at the school. In a series of linked short stories that start in the Showa era, go through the Heisei era and end in the Reiwa era, several generations of high school students are depicted as they worry about their home lives and their futures. Ibuki writes novels that can best be described as “heartwarming,” and you’re pretty much guaranteed happy endings with her books.

『お探し物は図書室まで』青山美智子

『お探し物は図書室まで』青山美智子

Searching at the Library, Michiko Aoyama

Another “heartwarming” novel, this is made up of five short stories about people who find their way by accident to a small library in a community house. The rather perfunctory reference librarian there gives them a book list that matches their requests, but there’s always an extra book on the list (for example, the children’s book “Guri to Gura” along with books on computer basics), which help to solve their problems. The librarian’s message is that it’s not the book itself that is so miraculous—the value comes from the way in which the reader interprets it.

『推し、燃ゆ』宇佐見りん

『推し、燃ゆ』宇佐見りん

Idol, Burned, by Rin Usami

This novella just won the 164th Akutagawa Prize, so it is bound to get a lot of attention even without this additional push from booksellers. Rin Usami is currently in her second year of university (majoring in Japanese literature of course), but has already won the Bungei Prize and the Yukio Mishima Prize for her debut novel, “Kaka.” “Idol, Burned” tells the story of Akari, a high school student who has a hard time knowing how to behave both within her family and at school. She finds purpose and some relief from the lassitude and heaviness she always seems to feel by supporting a male idol. Akari’s life begins to fall apart when he hits a female fan and comes under harsh criticism on social media. I’m reading this now and Usami is particularly brilliant at showing why people become so obsessed with a particular entertainer.

『オルタネート』加藤シゲアキ

『オルタネート』加藤シゲアキ

Alternate, by Shigeaki Kato

The author is a member of the J-pop group NEWS, part of the Johnny’s stable of performers (apparently when he finally got around to telling the other members of his group that he had written a novel, one said that he didn’t know what to think since he doesn’t read). “Alternate” was also nominated for the Naoki Prize. Kato’s novel is set at a high school in Tokyo, where Alternate, a matching app specifically for high school students, is widely used. The story of three high school students explores the meaning of family, friendship and the connections between people.

『逆ソクラテス』伊坂幸太郎

『逆ソクラテス』伊坂幸太郎

“Reverse Socrates,” Kotaro Isaka

Many readers are claiming that this is Isaka’s best novel so far. Set in an elementary school, in each of the five linked stories the children have to solve problems without easy answers. In one, students try to make their teacher realize his own biases and assumptions, and in another two boys look for evidence to prove that their classmate is being abused by his step-father.

『この本を盗む者は』深緑野分

『この本を盗む者は』深緑野分

“Who Stole This Book,” Nowaki Fukamidori

In this fantasy, Mifuyu, a high school student, hates books but her great-grandfather is a book collector and her father manages his massive warehouse of books. Anyone who steals a book will set a curse into motion, pulling the entire town into the world of that book. That’s exactly what happens, and Mifuyu has to search for the thief before her town is entirely subsumed. This town sounds like a booklover’s dream: it has a privately-run library, many bookstores, and a temple dedicated to the god of books!

『52ヘルツのクジラたち』町田そのこ

『52ヘルツのクジラたち』町田そのこ

The 52-hertz Whales, by Sonoko Machida

The “52-hertz whale” is the name that scientists gave to a whale that was first detected in the 1980s that calls at the frequency of 52 hertz. This is so much higher than the frequency used by other whale species that this whale cannot communicate with other whales and is thus known as the “world’s loneliest whale.” In this book, the main character, Kiko, has been abused by her parents for many years until finally someone helps her break away from her family. She cuts off all ties and moves to the country, but hadn’t realized that she would be subjected to intense curiosity in this atmosphere. She encounters a young boy who doesn’t talk and begins to wonder if he is being abused by his parents as she was. In addition to abused children, there are also characters dealing with domestic violence and transgender issues—people who feel like they’re screaming to get the world’s attention and yet not being heard.

『自転しながら公転する』山本文緒

『自転しながら公転する』山本文緒

Spinning while revolving, by Fumio Yamamoto

This is Yamamoto’s first book in seven years so I am really looking forward to it. Miyako is a 32 year-old who moves from Tokyo back to Ibaraki to care for her parents. With limited options for work, she takes a job working at a store in an outlet mall on a contract basis. All of her friends are getting married or have boyfriends, but Miyako ends up dating a man who is clearly not “marriage material.” Her parents’ health worsens, as does their financial situation, and Miyako experiences sexual harassment and power harassment at work. Yamamoto wrote that she has always felt that everyone but herself is skillful and able to juggle while dancing gracefully, whereas she is constantly beating herself up for being unable to do more. But recently she realized that behind the scenes, everyone is probably struggling. Yamamoto wanted to write a novel that reflected the way we are always rushing about with no time to stand still, leading busy lives and yet unexpectedly bored inside.

『八月の銀の雪』伊与原新

『八月の銀の雪』伊与原新

Silver Snow in August, by Shin Iyohara

This is a collection of five short stories, including one about an encounter between a Vietnamese employee at a convenience store and a university student struggling to find a job. Another is about a middle-aged man who has quit his job and is traveling alone, and encounters an older man whose father had been a meteorologist in WWII. All of these stories are about our relationship with the environment and nature, whether that is a pigeon’s homing instinct or the jet stream across the Pacific.

『滅びの前のシャングリラ』凪良ゆう

『滅びの前のシャングリラ』凪良ゆう

Shangri-La Before the End, Yu Nagira

Nagira certainly doesn’t mess around with light and comforting topics! Her previous book, 『流浪の月』(The Roving Moon), which won last year’s Booksellers Award, was about a neglected, sexually abused girl who finds temporary refuge with a young man who is accused of being a pedophile and kidnapper when she is found. Her latest novel is about four people who have never been able to figure out their lives, and now have to learn how to live when they learn that an asteroid will destroy the Earth in one month. The characters are wide-ranging, including a boy who is being bulled in school, a yakuza who has killed people, and a young woman carefully raised in a wealthy home but left unfulfilled. The world is about to end, and yet these four interlinked stories are about individuals rebuilding their lives.

「高円寺古本酒場ものがたり」狩野俊

「高円寺古本酒場ものがたり」狩野俊 The first part of the book consists of diary entries in which Karino describes his working days, which often seem to be more about massive amounts of alcohol and his tendency to skip out on work than actual day-to-day operations. The reader could be forgiven for wondering if he even has many customers (or wants any). One diary entry is simply a notice of the bar’s closure for a holiday, which he begins by saying that he hasn’t been able to read books recently because he hasn’t had the time (which he admits is a well-worn excuse), and all he wants is a quiet, civilized life in which he can drink Shiranami sake (a cheap brand of sake) from the morning without getting falling-down drunk. And so he is closing the bar for a summer break during which he will “sleep, think, and when I get tired of that, walk around town, go to an izakaya in the evening, shed the alcohol from my body, sleep again, wake up and walk.” Karino never seems to have much problem justifying random days off; in another entry, he describes how he’ll often close the shop to go walking in places like Kichijoji and Mitaka. His rest stops during these walks are sento (public bath), which he finds by walking with his gaze directed up toward the sky so he can spot the tell-tale smokestack of a sento.

The first part of the book consists of diary entries in which Karino describes his working days, which often seem to be more about massive amounts of alcohol and his tendency to skip out on work than actual day-to-day operations. The reader could be forgiven for wondering if he even has many customers (or wants any). One diary entry is simply a notice of the bar’s closure for a holiday, which he begins by saying that he hasn’t been able to read books recently because he hasn’t had the time (which he admits is a well-worn excuse), and all he wants is a quiet, civilized life in which he can drink Shiranami sake (a cheap brand of sake) from the morning without getting falling-down drunk. And so he is closing the bar for a summer break during which he will “sleep, think, and when I get tired of that, walk around town, go to an izakaya in the evening, shed the alcohol from my body, sleep again, wake up and walk.” Karino never seems to have much problem justifying random days off; in another entry, he describes how he’ll often close the shop to go walking in places like Kichijoji and Mitaka. His rest stops during these walks are sento (public bath), which he finds by walking with his gaze directed up toward the sky so he can spot the tell-tale smokestack of a sento.

Lest we should make the mistaken assumption that running a bookstore/izakaya is too idyllic, Karino follows up these diary entries with three essays on how he came to start his bookstore and his subsequent moves. After working for two years at a secondhand bookstore, this store closed due to poor sales, so he somehow decided that the logical thing to do was to open his own store. He chose Kunitachi as a location simply because his girlfriend lived there and there were plenty of izakaya, as well as a famous roast giblet restaurant, in the neighborhood, so he figured he could have fun after work. He didn’t even look into whether there were other secondhand bookstores in the area. Karino also had no idea how to get financing for his venture, but went to the bookstore (naturally) to research this and learned about the National Finance Corporation, which made loans to individuals and small companies starting businesses. The biggest difficulty in getting a loan was finding a co-signer (normally a family member). In the article he read, the author used an agency that found him a proxy, so Karino decided to go this route too. The agencies he called all seemed dodgy and charged steep fees, but he finally found an agency that seemed more trustworthy, and although the man initially said they didn’t take on loans for such low amounts (Karino wanted to borrow ¥2,000,000, or roughly $19,312 at the current exchange rate), when he heard it was for a bookstore, he made an exception because his father had run a bookstore. This is the kind of lucky break that so frequently seems to save Karino from his rather casual attitude toward business. Karino ended up getting the loan with this broker’s help, but several years later, he was watching the news when he saw his face on the TV screen—he had been arrested for fraud.

Lest we should make the mistaken assumption that running a bookstore/izakaya is too idyllic, Karino follows up these diary entries with three essays on how he came to start his bookstore and his subsequent moves. After working for two years at a secondhand bookstore, this store closed due to poor sales, so he somehow decided that the logical thing to do was to open his own store. He chose Kunitachi as a location simply because his girlfriend lived there and there were plenty of izakaya, as well as a famous roast giblet restaurant, in the neighborhood, so he figured he could have fun after work. He didn’t even look into whether there were other secondhand bookstores in the area. Karino also had no idea how to get financing for his venture, but went to the bookstore (naturally) to research this and learned about the National Finance Corporation, which made loans to individuals and small companies starting businesses. The biggest difficulty in getting a loan was finding a co-signer (normally a family member). In the article he read, the author used an agency that found him a proxy, so Karino decided to go this route too. The agencies he called all seemed dodgy and charged steep fees, but he finally found an agency that seemed more trustworthy, and although the man initially said they didn’t take on loans for such low amounts (Karino wanted to borrow ¥2,000,000, or roughly $19,312 at the current exchange rate), when he heard it was for a bookstore, he made an exception because his father had run a bookstore. This is the kind of lucky break that so frequently seems to save Karino from his rather casual attitude toward business. Karino ended up getting the loan with this broker’s help, but several years later, he was watching the news when he saw his face on the TV screen—he had been arrested for fraud. In another typical predicament, the night before Karino was supposed to open his bookstore, all the shelves were in place, but they were barely full. He didn’t have enough stock, even though he had grudgingly used all of his own books and his girlfriend had contributed hers as well. Luckily, they realized that the next day was the recyclable garbage collection day, so people would be putting out books. Cans of beer in one hand, they pushed a cart through the Kunitachi neighborhood and collected books and magazines (imagine the surprise of customers who find the very same books they had put out with the garbage now on a bookstore’s shelves!).

In another typical predicament, the night before Karino was supposed to open his bookstore, all the shelves were in place, but they were barely full. He didn’t have enough stock, even though he had grudgingly used all of his own books and his girlfriend had contributed hers as well. Luckily, they realized that the next day was the recyclable garbage collection day, so people would be putting out books. Cans of beer in one hand, they pushed a cart through the Kunitachi neighborhood and collected books and magazines (imagine the surprise of customers who find the very same books they had put out with the garbage now on a bookstore’s shelves!).

Recent Comments