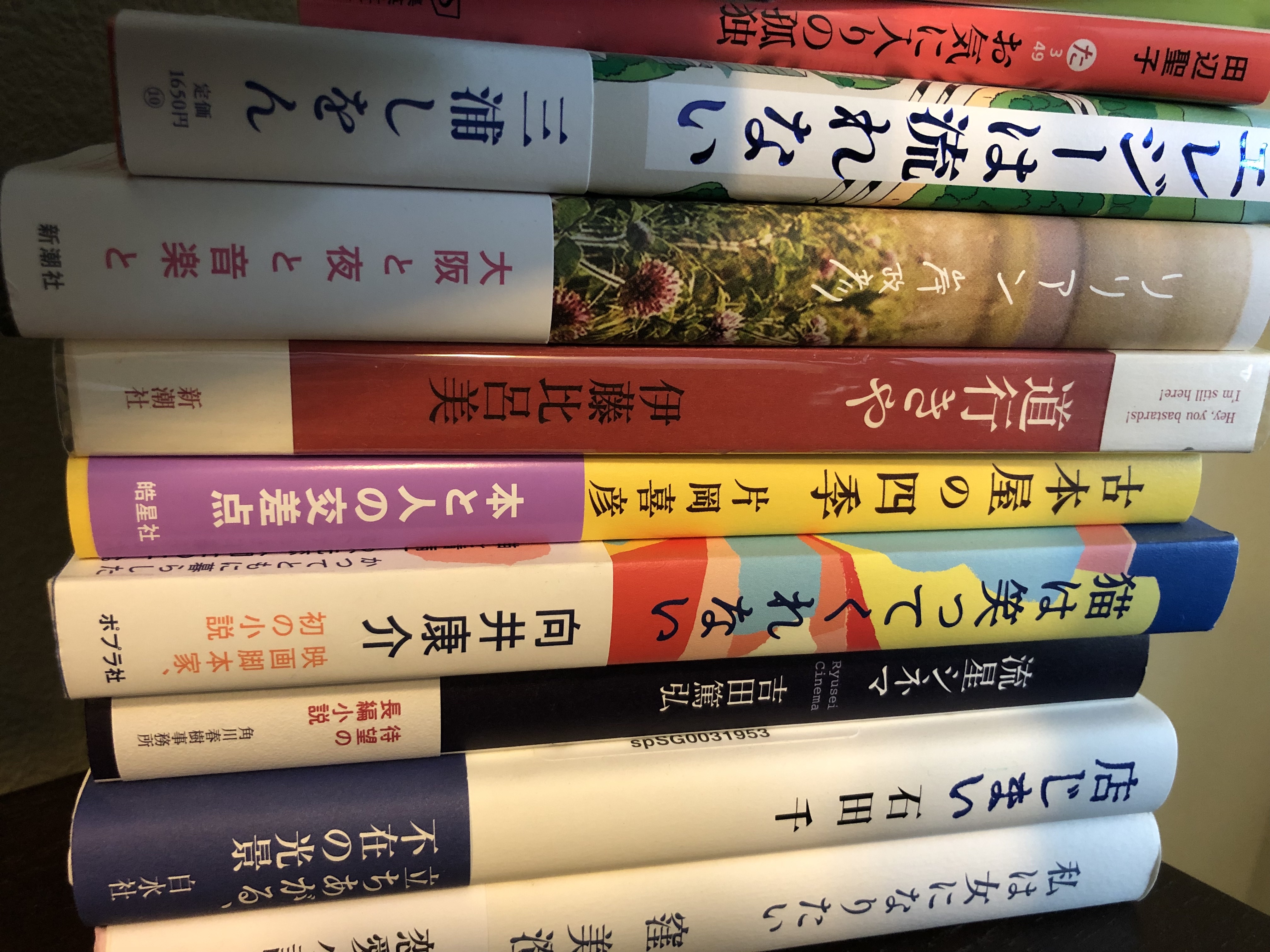

東京の子、藤井 太洋 、Kadokawa 2019

東京の子、藤井 太洋 、Kadokawa 2019

Tokyo Nipper, by Taiyo Fujii

Novels set in the future and other science fiction are often used to express our deepest fears about human nature and technology, but in Tokyo Nipper, Taiyo Fujii focuses on our brighter possibilities. In an interview, Fujii said that he doesn’t think we have to be so pessimistic about the future since, in his eyes, the world has improved in so many ways over the past 30 years. In his novels, he wants to create a sense that there is nothing embarrassing about speaking idealistically.

And his vision of Tokyo in 2023, three years after the Olympics, is very bold and optimistic. The government, left with sports facilities that had become liabilities and would have to be dismantled or repurposed at further taxpayer expense, decided instead to sell the land to the private sector, which then transformed the facilities into shopping malls, huge warehouses, tower condominiums, nursing homes and universities. It was foreigners who provided the labor, allowed in under Japan’s “foreign technician training system” and “highly-skilled professional system.” In Fujii’s version of history, the government had revised the immigration law in 2019 to significantly expand these two programs so that foreigners could work in Japan not only as IT engineers, civil engineers and nurses, but also as supermarket and convenience store staff and garbage collectors. Making the picture even rosier, Fujii writes that Southeast Asia’s economic growth means that foreign workers no longer work for miserable wages, but now expect the same pay as Japanese. This has increased Tokyo’s population from 13 million to 16 million in the three years following the Olympics and foreigners accounted for all three million.

The ruins of the bobsled track used for the Sarajevo Olympics. Source: Getty Images

Fujii also gives us a hero who is just as interesting as the new Tokyo he occupies. Isamu Karibe lives above a Vietnamese restaurant and makes a living by finding foreigners who have stopped showing up for work and convincing them to go back to work. Just like these foreigners, Karibe lacks roots. “Karibe” isn’t even his own name—he bought a family registry so his parents, who neglected him until he nearly starved as a baby, could never find him. The children in the institution he grew up in are given Korean-made smartphones by Okuma, a yakuza looking for new revenue streams (he paid them pocket change for repeatedly reloading websites to increase views and clicking on ads for adult videos). It was Okuma who helped Karibe make parkour videos in the early days of YouTube, making him one of its first stars. Karibe still uses parkour to chase foreigners. The description of parkour moves give the novel a dynamism that Japan’s aging, static society seems to lack in reality.

Photograph by Gabe L’Heureux

This is matched by the verve of the students—they even hold demonstrations and protests!—that Karibe meets at Tokyo Dual, a polytech with 40,000 students that has been built on a former Olympic site. The students study while also working for the “supporter” companies that have offices and factories on site. They earn salaries and can even go on to work fulltime for these companies after graduating. In this brave new world Fujii has created, supporter companies can fire students easily and students can change jobs at will.

Karibe’s assignment at the start of this novel is to find a Vietnamese girl who isn’t showing up for work or classes. In this search, he uncovers allegations of human trafficking and learns of a new law allowing Chinese to be forcibly deported. Unfortunately, I didn’t find this as interesting as Fujii’s world creation, and the parkour and the vitality of this Tokyo weren’t enough to make up for leaden dialogue and some confusing plot developments.

Fujii has said that this future is entirely possible, given that the government did in fact pass a law easing immigration rules for workers in December 2018. The resistance to these modest changes (Japan still prefers migrants who will go home some day over immigrants) makes me skeptical. Still, I think Fujii really just wants to start a conversation about possibilities, and I hope people are listening.

Source: Anouchka Noisillier

Recent Comments