横道世之介、吉田修一、毎日新聞社、2009

横道世之介、吉田修一、毎日新聞社、2009

Yokomichi Yonosuke, by Shuichi Yoshida; Mainichi Shimbun, 2009

[not available in English translation; Yoshida’s mysteries Villain and Parade have been translated, but are quite different in tone and subject matter than this novel]

This exuberant novel tells the story of one year in the life of Yonosuke Yokomichi, who leaves the small town he grew up in to attend college in Tokyo in 1987. He is neither especially good-looking nor particularly smart, but a combination of fortuitous events and his eagerness to grab them shape his life. A student he meets during college orientation forces him to join the samba club with him, which in turn leads to a referral from a fellow member for a job at a luxury hotel, delivering room service on the night shift. An employee there gives him a box of porn videos, which he then uses to convince a friend to take a kitten he finds abandoned in the alley. On Valentine’s Day, a box of chocolates is delivered to his mailbox by accident, and he resolves to visit every apartment in his building until he finds their rightful owner. This leads him to a photographer, who ends up lending him an old Lycra and thus essentially launches Yonosuke’s career as a photographer. He agrees to go on a double date with a friend and meets Shoko, a young girl from a wealthy family who falls for him. As she says much later, Yonosuke is not particularly impressive, but he was the “kind of person who said ‘yes’ to everything.”

The poster for the 2013 film of Yonosuke Yokomichi, starring Kengo Kora as Yonosuke and Yuriko Yoshitaka as Shoko

Yonosuke can be quite unaware, and doesn’t always know when he’s not wanted. He spends half of his summer vacation at his friend Kato’s air-conditioned apartment, immune to Kato’s not-so-veiled hints that he is not entirely welcome. There’s a particularly funny scene when Kato announces that he’s going for a walk, even though it’s almost midnight. Without waiting to be invited, Yonosuke picks up half of a watermelon and announces that he’ll accompany Kato, even though he’s obviously not wanted. He follows the half-disgruntled, half-resigned Kato, cradling the watermelon and eating it with a spoon. Their conversation is a perfect illustration of Yonosuke’s mix of obtuseness and good nature.

After walking about three minutes, Kato suddenly stops and asks, “You remember when I said that I’m not interested in girls?”

“Oh yeah, I remember that.”

“And then you said this was the first time you’d ever met anyone your age like that and asked what I was interested in.’”

“Sure, that sounds right.”

“Well, I like men better than women.” Kato spoke brusquely, and yet he was surprisingly nervous.

“Oh, yeah?”

“What do you mean, ‘oh, yeah?’ That’s all you have to say?” Kato was more taken aback than Yonosuke seemed to be.

“Wait, hold on… Did you ever mess around with me while I was sleeping?”

“Of course not! You’re not my type.”

“Geez, that’s so rude!”

“That’s just the way it is. What I’m trying to say is, if you don’t want to hang out with me anymore, I’ll understand.”

Kato begins walking again.

“Is that a roundabout way of telling me not to stay over anymore?” Now Yonosuke is alarmed.

“That’s not what I’m saying! But hold on a minute here– you’re not even a little disturbed?”

“Of course I am! For a minute there I thought I was going to lose my access to air conditioning!”

“And that’s all you’re upset about?!”

“Yup.”

“Well, that’s what I wanted to say.”

“Got it. So I can still stay at your place, right?”

It turns out that Kato is going to a park, well supplied with bushes and trees, where men go for illicit trysts. When Kato finally makes Yonosuke understand this, instead of going home, as Kato had expected, Yonosuke sits on a park bench, finishes off his watermelon and waits for Kato.

Yonosuke in one of his clueless moments

In an interview, author Shuichi Yoshida said that he is more attached to Yonosuke than any other character in his books. He is even jealous of Yonosuke, since he gave him attributes that he doesn’t have himself, such as a total lack of pretense. Completely unselfconscious, he manages to draw the best from others. Yoshida shows this by interspersing the main narrative, set in 1987-88, with the reflections of people who knew him. They recall him with nostalgia and even a sense of yearning from a vantage point of 20 years. His friend Kato muses, “His life probably wouldn’t have been any different if he hadn’t met Yonosuke. But most people in this world had never had the chance to meet Yonosuke in their youth, and this made him feel that he’d been lucky.” By itself, this would be a very entertaining story, but these voices make it achingly tender at times.

Shuichi Yoshida was inspired to write this book by an actual event, and so I cannot do justice to his writing without “spoilers” (although the reveal comes about halfway through the book). However, in this case I don’t think that knowing Yonosuke’s fate spoils the reading experience—if anything, it lends the story more poignancy.

This book was modeled on an accident at Shin-Okubo Station on the Yamanote Line, one of Tokyo’s busiest train lines, on January 26, 2001. Seiko Sakamoto, a 37 year-old plasterer, was drinking on the platform with a friend and fell onto the tracks. Lee Su Hyon, a 26 year-old South Korean exchange student who attended language school in Tokyo, and Shiro Sekine, a 47 year-old photographer, jumped onto the line to try and rescue Sakamoto, but all three were killed by an oncoming train. I was living in Japan at the time, and have never forgotten these two men. The news coverage was extensive, in part because of the soul-searching it inspired across Japan. Newspaper editorials and panels of experts convened for Sunday news shows asked why it had been a South Korean man (whose grandfather had been a forced laborer in Japan’s coal mines, no less) and a photographer (who had spent much of his career overseas) who tried to save Sakamoto, and not any of the other people on the train platform (not even the friend who was with him). The following week two men dragged a schoolboy attempting suicide off the railway in Nagoya, and a pregnant woman who fell onto the tracks was also rescued in Tokyo*. Yoshida said that although this was a terrible event, it had left him with a “refreshing sense of hope,” and perhaps this is what he was hoping for.

This book was modeled on an accident at Shin-Okubo Station on the Yamanote Line, one of Tokyo’s busiest train lines, on January 26, 2001. Seiko Sakamoto, a 37 year-old plasterer, was drinking on the platform with a friend and fell onto the tracks. Lee Su Hyon, a 26 year-old South Korean exchange student who attended language school in Tokyo, and Shiro Sekine, a 47 year-old photographer, jumped onto the line to try and rescue Sakamoto, but all three were killed by an oncoming train. I was living in Japan at the time, and have never forgotten these two men. The news coverage was extensive, in part because of the soul-searching it inspired across Japan. Newspaper editorials and panels of experts convened for Sunday news shows asked why it had been a South Korean man (whose grandfather had been a forced laborer in Japan’s coal mines, no less) and a photographer (who had spent much of his career overseas) who tried to save Sakamoto, and not any of the other people on the train platform (not even the friend who was with him). The following week two men dragged a schoolboy attempting suicide off the railway in Nagoya, and a pregnant woman who fell onto the tracks was also rescued in Tokyo*. Yoshida said that although this was a terrible event, it had left him with a “refreshing sense of hope,” and perhaps this is what he was hoping for.

Plaque erected at Shin-Okubo Station to honor Lee Su Hyon and Shiro Sekine

We find out about Yonosuke’s death midway through the book. Yoshida slips in a reference to the recent collapse of Lehman Brothers to alert us that we have left 1987 and jumped ahead to 2008. Chiharu, a woman rumored to be a high-end call girl whom Yonosuke had pursued, now has her own show on a radio station. Her assistant director comes in during her show with breaking news for Chiharu to announce: a fatal accident at Yoyogi Station has forced the closure of the Yamanote line’s inner loop, with severe delays on the outer loop. Driving through the city in a taxi later that night, she hears a more detailed news report on the radio, and learns that Park Seung Jun, a 26 year-old South Korean exchange student, and Yonosuke Yokomichi, a 40 year-old photographer, had jumped onto the tracks to save a girl who had fainted and fallen onto the tracks, but were hit by an oncoming train. When her companion asks her why she has become so silent, Chiharu says she is trying to remember something, but it keeps slipping away. With that, Yoshida returns the reader to 1987 and Yonosuke, practicing samba in a laundromat to the rhythm of the driers.

Yonosuke in his samba costume

Yoshida also seems to foreshadow Yonosuke’s death. Yonosuke recalls the first time he had a clear perception of death. Standing on the platform of Shinjuku Station for the first time, he walked along the white safety line and heard the announcement for the incoming train. As the train swooped past, just inches away from him, he sensed that just a few inches to the left would put him over the dividing line between life and death.

Even more strikingly, close to the end of the book, Yonosuke bumps into an acquaintance, a young Korean exchange student. As they wait at Shin-Okubo Station together, a hat blows off a woman’s head just as a train approaches. Both Yonosuke and Kim dash after the hat as it careens down the platform. Before they fall off of the platform onto the tracks, one of them grabs the other—in all the confusion, it is not clear who is holding who back. Everything seems to move in slow motion as the train enters the station and, miraculously, the wind pressure from the incoming train blows the hat right to their feet.

I read this book last summer, but the story and the Shin-Okubo accident left such an impression on me that since then I have struggled to do the book justice. I had to prune several pages off of this review as my enthusiasm for this book got the better of me. Maybe Yonosuke (and Lee Su Hyon and Shiro Sekine) didn’t get to live out his life, but if this book is anything to go by, in his 40 years he lived more fully than many who are granted the full threescore and ten do.

I can’t do any better than leave the closing words to Yonosuke’s mother, who writes in a letter to Shoko:

Lately I’ve realized that I was lucky to have Yonosuke as my son. Maybe it’s a strange thing for a mother to say, but meeting him was the best thing that happened to me. I still envision the accident in my head a lot. I can’t figure out why he jumped onto the tracks even though there was no way he could save her. But lately I’ve realized that Yonosuke must have been convinced he could help. In that instant, he thought “I can do this,” not, “it’s no use, there’s nothing I can do.” And I’m very proud to have a son who thought in this way.

The parents of Lee Su-hyon, Lee Sung-dae and Shin Yoon-chan (right), pray on the platform of JR Shin-Okubo Station in Tokyo at a ceremony to honor their son in 2013, attended by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and then-South Korean President Park Geun-hye; Photograph by Yoshiaki Miura for Japan Times

*Since this accident, safety barriers and doors have been installed at many train stations, but only about 30% of Japan’s 250 largest train stations had these safety measures as of 2016. Emergency stop buttons have also been installed at thousands of train stations. After discovering that Seiko Sakamoto, the drunk man who fell onto the tracks, was drinking sake he had bought at a vending machine in the station itself, authorities decided to remove alcohol from “some” vending machines.

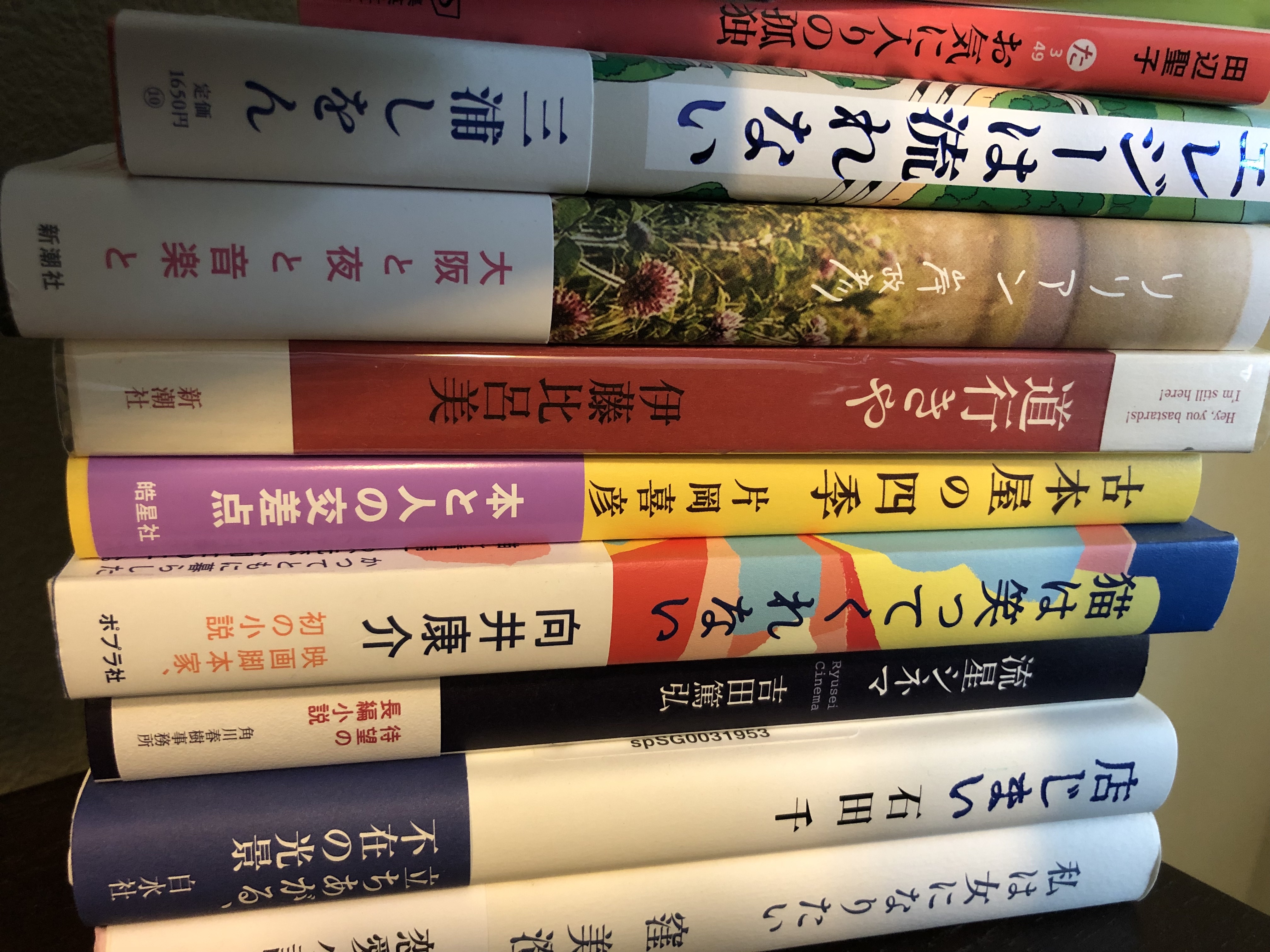

『i』、西加奈子(著)、ポプラ社

『i』、西加奈子(著)、ポプラ社 『暗幕のゲルニカ』、原田マハ(著)、新潮社

『暗幕のゲルニカ』、原田マハ(著)、新潮社 『桜風堂ものがたり』、村山早紀(著)、PHP研究所

『桜風堂ものがたり』、村山早紀(著)、PHP研究所 『コーヒーが冷めないうちに』、川口俊和(著)、サンマーク出版

『コーヒーが冷めないうちに』、川口俊和(著)、サンマーク出版 『コンビニ人間』、村田沙耶香(著)、文藝春秋

『コンビニ人間』、村田沙耶香(著)、文藝春秋 『ツバキ文具店』、小川糸(著)、幻冬舎

『ツバキ文具店』、小川糸(著)、幻冬舎 『罪の声』、塩田武士(著)、講談社

『罪の声』、塩田武士(著)、講談社 『みかづき』、森絵都(著)、集英社

『みかづき』、森絵都(著)、集英社 『蜜蜂と遠雷』、恩田陸(著)、幻冬舎

『蜜蜂と遠雷』、恩田陸(著)、幻冬舎 『夜行』、森見登美彦(著)、小学館

『夜行』、森見登美彦(著)、小学館 コンビニ人間

コンビニ人間

I admit I got a bit tired of the use of the forest as metaphor, but Miyashita’s descriptions of Tomura’s growing awareness of the beauty around him were lovely. When he has a free moment, Tomura opens the lid of the piano and gazes inside at the 88 piano keys and the strings attached to each one. The strings stretched out straight and the hammers lying ready to strike look like an orderly forest to him. He sees beauty here, something that had just been an intellectual concept to him before.

I admit I got a bit tired of the use of the forest as metaphor, but Miyashita’s descriptions of Tomura’s growing awareness of the beauty around him were lovely. When he has a free moment, Tomura opens the lid of the piano and gazes inside at the 88 piano keys and the strings attached to each one. The strings stretched out straight and the hammers lying ready to strike look like an orderly forest to him. He sees beauty here, something that had just been an intellectual concept to him before. 「私の小さな古本屋」

「私の小さな古本屋」

Over the years, the stock in her bookstore has come to reflect this community since about 90% of her stock consists of books she buys from her customers. People with similar interests buy books in her store and sell their books to her in turn, occasioning comments from customers that visiting her store is like looking at their own bookshelves.

Over the years, the stock in her bookstore has come to reflect this community since about 90% of her stock consists of books she buys from her customers. People with similar interests buy books in her store and sell their books to her in turn, occasioning comments from customers that visiting her store is like looking at their own bookshelves.

Coincidentally, around the same time I was reading this book I picked up a manga that illustrates Hojo’s reporting. Aoi Ikebe’s プリンセスメゾン (Princess Maison) tells the story of Numa-chan, a young woman who works in a pub and yet, despite her low wages and unmarried status, wants to buy her own apartment. Impressed with her persistence, the employees of a real estate company she frequents befriend her and help with her search.

Coincidentally, around the same time I was reading this book I picked up a manga that illustrates Hojo’s reporting. Aoi Ikebe’s プリンセスメゾン (Princess Maison) tells the story of Numa-chan, a young woman who works in a pub and yet, despite her low wages and unmarried status, wants to buy her own apartment. Impressed with her persistence, the employees of a real estate company she frequents befriend her and help with her search.

Recent Comments