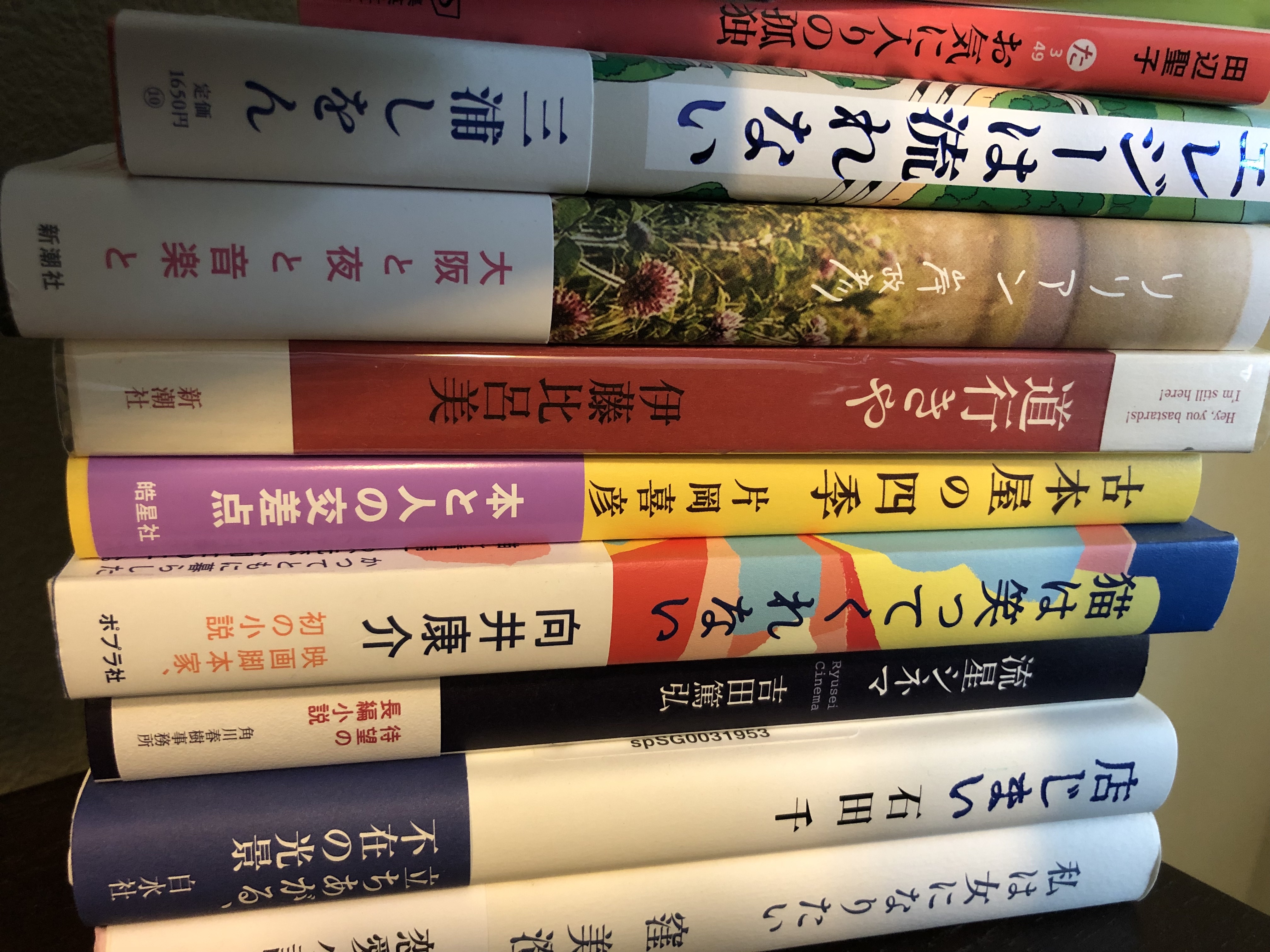

The 10 books nominated for the 2018 Booksellers Award were announced on January 2018. One of the reasons I look forward to this list so much is the sheer variety of the selections. After all, the titles are chosen by bookstore clerks who are eager to promote their favorites, so I think this is as close as we can get to an award given by people who are readers first and foremost. This year the list is as eclectic as ever, with novels about zombies, the intersections between Japanese art and French Impressionism, the struggles of the publishing industry, a murder involving the game of shogi, bullying, a professional assassin, a modern-day scribe, a mysterious brain cancer patient, and a failing department store (with a cat thrown in for good measure).

『AX アックス』、伊坂幸太郎

AX, by Kotaro Isaka

Isaka, a mystery writer who has won many awards, has said that he writes to deal with his constant fear that something horrible is going to happen and that these catastrophes will change Japan irrevocably. “AX” is about a highly skilled professional assassin who continues to take jobs until he has enough money for retirement. In contrast to his professional mien, he cannot stand up to his wife at home and doesn’t even have the respect of his son. While you’re waiting for this to be translated, you could try Isaka’s novel, ゴールデンスランバー, published in an English translation by Stephen Snyder under the title Remote Control, about a young man who is framed for the murder of the Japanese prime minister and tries to escape.

『かがみの孤城』 、辻村深月

The Solitary Castle in the Mirror, by Mizuki Tsujimura

The Solitary Castle in the Mirror, by Mizuki Tsujimura

This long novel is about a young girl who has stopped going to school because she is being bullied. One day, she notices that the mirror in her bedroom is glowing, and as she reaches out to touch it, she is pulled through the mirror and into a game, supervised by a young girl wearing a wolf mask. Kokoro and six other children in similar situations have one year to search a castle for a key that will grant the finder a wish. I will read anything Tsujimura writes. I don’t read her books for the plots, I read them for her vivid characters and their relationships with each other. This book is worth reading if only for the back-and-forth between the prickly young girl leading this group and the fragile kids she tries to guide in their search.

『キラキラ共和国』、小川糸

『キラキラ共和国』、小川糸

The Sparkling Republic, by Ito Ogawa

This is a sequel to last year’s “Tsubaki Stationery Store,” also nominated for the 2017 Japanese Booksellers Award. This book continues Hatoko’s story and her life in Kamakura, interspersed with the predicaments and letters of the people who come to her for help writing letters.

『崩れる脳を抱きしめて』、知念実希人

Hold Tight to the Collapsing Brain, by Mikito Chinen

Chinen is a practicing doctor who writes mysteries and thrillers set in hospitals. This rather bizarre title is no exception—his other books have titles like “How to Keep a Pet Guardian of Death” (優しい死神の飼い方)and “Hospital Ward: The Masked Bandit” (仮面病棟). This novel is about Usui, a young man completing his medical residency when he meets Yukari, a young girl with brain cancer. They become close, but when he returns to his hometown, he is told that she has died. Billed as a love story wrapped in a mystery, Usui struggles to discover why Yukari has died and whether she ever existed in the first place.

『屍人荘の殺人』、今村昌弘

Murderers at the House of the Living Dead, by Masahiro Imamura

Murderers at the House of the Living Dead, by Masahiro Imamura

Members of a university’s mystery club travel together to stay at a pension, and find themselves forced to barricade themselves inside on the very first night. The very next morning, one of their members is found dead, in a locked room. This mystery takes some of the elements of a locked-room murder, but adds zombies to the mix. Reviews have been mixed, with my favorite being from someone who wrote that he felt like he had ordered curry rice, and was served with curry udon instead.

『騙し絵の牙』、塩田武士

The Fang in the Trick Picture, by Takeshi Shiota

The Fang in the Trick Picture, by Takeshi Shiota

This novel follows Hayami, a magazine editor at a major publisher, as he desperately tries to keep his magazine from being discontinued. Hayami struggles with internal politics, but also faces the fight within the entertainment industry for our attention. I plan to read this one on the strength of Shiota’s previous novel based on the unsolved Glico-Morinaga case, “The Voice of the Crime” (also shortlisted for the 2017 award).

『たゆたえども沈まず』、原田マハ

“Fluctuat nec mergitur,” by Maha Harada

(The title refers to the Latin phrase used by Paris as its motto since 1358, meaning something like “tossed by the waves but never sunk.”)

In this novel, Harada has used the historical figure Tadamasa Hayashi, a Japanese art dealer who went on to introduce ukiyo-e, woodblock prints and other forms of Japanese art to Europe, as a way to explore the question of why Japan is so fascinated with Vincent van Gogh. Harada believes that the explanation lies in elements of ukiyo-e in van Gogh’s paintings, and although there is no evidence that Hayashi and van Gogh ever met, this novel imagines a friendship between Hayashi and and Theo and Vincent van Gogh that changed Impressionism.

Harada was also nominated last year for『暗幕のゲルニカ』(Guernica Undercover), about Picasso’s Guernica painting.

『盤上の向日葵』、柚月裕子

“The Sunflower on the Shogi Board,” by Yuko Yuzuki

“The Sunflower on the Shogi Board,” by Yuko Yuzuki

The book starts in 1994 with the discovery of skeletal remains buried with a piece from a famous shogi set (shogi is a Japanese game similar to chess). Naoya Sano, a policeman who had aspired to be a professional shogi player, and veteran detective Tsuyoshi Ishiba try to identify the body. Their search alternates with the story of Keisuke, starting in 1971. Keisuke’s mother has died and his father abuses him, but a former teacher recognizes his unusual talent for shogi and encourages him to leave for Tokyo and become a professional.

This book is especially timely as shogi has been in the headlines a lot lately thanks to the amazing wins of fifteen-year-old Sota Fujii, Japan’s youngest professional shogi player. There has actually been a run on shogi sets, which has to be a first!

『百貨の魔法』、村山早紀

The Department Store’s Magic, by Saki Murayama

The Department Store’s Magic, by Saki Murayama

This book is a series of interlinked stories about the people who work at a local department store: the elevator girl, the concierge, the jewelry department’s floor manager and the founder’s family. As rumors about the store’s impending closure begin to go around, they all come together to try and save the store—with the help of the white cat who lives there. Murayama’s The Story of Ofudo (about a bookstore, and also involving a cat) was nominated for last year’s award, and I’ve been reading it when I need a respite from my current read, Fuminori Nakamura’s R帝国 (Empire R)—its fairytale atmosphere is a welcome contrast to Nakamura’s dark vision.

『星の子』、今村夏子

Child of the Stars, Natsuko Imamura

Child of the Stars, Natsuko Imamura

The narrator of this novel (which was also nominated for the Akutagawa Prize) is a third-year middle school student, Chihiro. She was born premature and began suffering from eczema when she was a baby. Her parents tried every treatment recommended, but with no effect. Finally, her father’s co-worker gives them a bottle of water labeled “Blessings of the Evening Star,” with instructions to wash her with it. This completely cures her, and her parents become wrapped up in this co-worker’s cult as a result. Although Chihiro’s older sister runs away, Chihiro is able to separate her home life from life outside—at least until she reaches adolescence.

And there you have it. The booksellers have spoken, and now we must do our part and get reading.

ツバキ文具店、小川糸、幻冬舎、2016

ツバキ文具店、小川糸、幻冬舎、2016

The fumizuka Hatoko cares for commemorates letters. From the third day of the new year, mail begins to pour in from all over Japan and even overseas from people who can’t bear to throw away letters themselves. Many of these letters are love letters that the recipients are unable to give up until just before they marry someone else. Some people even send all the letters they receive over the course of the year. On February 3, according to the lunar calendar, she burns the letters and preserves the ashes. This aligns with her family’s belief that letters are essentially an offshoot of the writer, the words infused with their breath. (Lest this sound too solemn an occasion, I should mention that a friend joined her for this winter bonfire and they roasted potatoes, Camembert cheese, rice balls and French bread in the embers.)

The fumizuka Hatoko cares for commemorates letters. From the third day of the new year, mail begins to pour in from all over Japan and even overseas from people who can’t bear to throw away letters themselves. Many of these letters are love letters that the recipients are unable to give up until just before they marry someone else. Some people even send all the letters they receive over the course of the year. On February 3, according to the lunar calendar, she burns the letters and preserves the ashes. This aligns with her family’s belief that letters are essentially an offshoot of the writer, the words infused with their breath. (Lest this sound too solemn an occasion, I should mention that a friend joined her for this winter bonfire and they roasted potatoes, Camembert cheese, rice balls and French bread in the embers.)

舟を編む、三浦しをん、光文社、2011

舟を編む、三浦しをん、光文社、2011 surface of the dark ocean, searching for the word that will most accurately and faithfully convey their thoughts to other people. Without dictionaries, people would just stand, wordless, in front of the ocean’s wide expanse.

surface of the dark ocean, searching for the word that will most accurately and faithfully convey their thoughts to other people. Without dictionaries, people would just stand, wordless, in front of the ocean’s wide expanse.

know exactly what he means—clearly Majime is suited to the work of compiling dictionaries. Just like commuters sorting themselves into queues, words are collected, classified, put into groups and organized in order on the pages of a dictionary.

know exactly what he means—clearly Majime is suited to the work of compiling dictionaries. Just like commuters sorting themselves into queues, words are collected, classified, put into groups and organized in order on the pages of a dictionary. find a goal that is worth such single-minded dedication? Nishioka watches Majime and Matsumoto spend their own money on reference materials and become so absorbed in their research that they miss the last train. Although he doesn’t understand this devotion, he likes being a part of this work, almost as if hoping that a bit of their enthusiasm would rub off on him.

find a goal that is worth such single-minded dedication? Nishioka watches Majime and Matsumoto spend their own money on reference materials and become so absorbed in their research that they miss the last train. Although he doesn’t understand this devotion, he likes being a part of this work, almost as if hoping that a bit of their enthusiasm would rub off on him.

I have read this book three times since it was first published in 2011, and have often wondered why it appeals to me so much (although it’s not just me—it won the 2012 Booksellers Award). We are all intrinsically drawn to fairy tales and legends, and there are certainly echoes here of the holy grail, the ugly duckling, and the pursuit of a seemingly unattainable princess. But I think that most of the appeal for me comes from the idea of a small department working with utter concentration and conviction for almost twenty years on a grand project. When my days are interrupted by breaking news stories flashing across my cellphone screen and the hours are broken down into neat blocks of time in my planner, a life in which you can miss the last train to keep researching a word seems like the ultimate luxury.

I have read this book three times since it was first published in 2011, and have often wondered why it appeals to me so much (although it’s not just me—it won the 2012 Booksellers Award). We are all intrinsically drawn to fairy tales and legends, and there are certainly echoes here of the holy grail, the ugly duckling, and the pursuit of a seemingly unattainable princess. But I think that most of the appeal for me comes from the idea of a small department working with utter concentration and conviction for almost twenty years on a grand project. When my days are interrupted by breaking news stories flashing across my cellphone screen and the hours are broken down into neat blocks of time in my planner, a life in which you can miss the last train to keep researching a word seems like the ultimate luxury.

Recent Comments