蜜蜂と遠雷、恩田陸、幻冬舎 2016

蜜蜂と遠雷、恩田陸、幻冬舎 2016

Honey Bees and Distant Thunder, Riku Onda, Gentosha, 2016

Honey Bees and Distant Thunder, which follows contestants in the Yoshigae International Piano Competition, has won both the 156th Naoki Prize and the 2017 Japanese Booksellers Award (the second time that Riku Onda has won this latter award). This is quite an achievement for a novel about the nature of genius and the role of music in the world. The Booksellers Award is determined based on votes by bookstore clerks around Japan who are asked to nominate three books that they would most like to recommend.

Booksellers Award ceremony; Source: Ibaraki News

Michiko, a judge in the Yoshigae Competition, is painfully aware that musicians invest so much time and money in their profession that no monetary compensation they earn during their career could make up for it. What they seek is a single moment of such perfect happiness and transcendence that it cancels out all of their struggles. The entire cast of characters in Honey Bees and Distant Thunder is caught up in the search for that moment.

The sheer number of characters, and the ways in which they are linked together and inspire each other, is one of the pleasures of this book. First there is Aya, who heard music in the sound of rustling leaves and the sound of galloping horses in the rain hitting the corrugated iron roof before she could even talk, and realizes that the world is always filled with music. She was a child prodigy, performing from a young age, but she ran off the stage in her first concert after her mother’s death and has kept her distance from the professional world ever since. Now in her last year of music school, she is returning to the stage for the first time, shepherded by her piano teacher’s daughter, Kanade.

Masaru Carlos, a Juilliard student with a Japanese-Peruvian mother and a French father, lived in Japan briefly as a child. It was Aya who essentially picked him up off the streets and dragged him with her to her piano lessons. When he moved to France, she made him promise that he would take piano lessons. They were so young that they didn’t even know each other’s full names, and their reunion in Yoshigae feels like a miracle. Masaru’s teacher and Kanade are both troubled and bemused by their lack of competitiveness and their respect for each other’s musicality.

Atsushi is the oldest competitor. He is married with a young child and works in a music store, but has been unable to forget his dream of playing professionally. He has stretched his finances to their limit to buy an upright piano for his home, build a soundproof room and pay a teacher for occasional advice, but the hardest part has been remaining motivated. All too often it seemed like a pointless exercise.

The pivotal character is probably Jin Kazama, who accompanies his bee keeper father around the world on his travels and doesn’t even own a piano. And yet he has a recommendation from one of the most eminent pianists in the world, the recently deceased Yuji Hoffman, which has earned him a place in this competition.

I bequeath Jin Kazama to all of you. He is a true gift, a gift from heaven for all of you. But don’t misunderstand. He is not the one being tested—it is myself, and you, that are being challenged. You will understand what I mean when you experience him yourself, but he is not an easily-digested bequest. He is a powerful tonic. Some of you will find him threatening, some of you will detest him and reject him. But this is part of his truth, and reveals the truth inside his listeners. It is up to you whether you accept him as an authentic gift or as a calamity.

A full lineup of supporting characters rounds out the cast. Michiko’s ex-husband, Nathaniel, is also at the competition, both as a judge and Masaru’s teacher. Michiko and Nathaniel serve the function of a Greek chorus, meeting in a bar at the end of the day to rehash everything from Hoffman’s intentions to the future of classical music. Then there is a documentary film maker, the piano tuner who works with Jin to recreate the sounds he hears in his head, the stage manager who ushers the competitors onto the stage and witnesses their nerves, and the ikebana teacher hosting Jin in Yoshigae.

Jin serves as a catalyst for all of these characters. His music touches on emotions that listeners had buried below the surface and forgotten. To some listeners, this feels like an invasion, while to others it is more like an awakening that reminds them of the beauty of music—not music as a profession or a commodity, but as an ideal that they’d lost sight of.

When Michiko heard him play, she sensed that there was something fundamentally different between him and the other contestants. They recreated the music and strived to play what was buried in the score, but Jin seemed to be trying to blot out the score and reach down to the core of the music. Initially, some listeners—and judges—see this as an insult to composers and musicians, but no matter how visceral their reaction, they all want to hear more. Jin’s gift—the gift that Hoffman left all of them—seems to have been his effect in drawing out everyone’s talents.

This is a placid group of geniuses, egos all well under control if they exist at all. Aya, Masaru and Jin walk on the beach together, Jin looking for the Fibonacci sequence in shells while they muse about whether there might be Mozarts and Beethovens on other stars. They fret about the growing commercialization of music and debate the fine line between entertainment and populism. The eccentricities of these musicians were charming and occasionally thought-provoking, but much of the book—which clocks in at over 500 pages—consists of long descriptions of every piece that Aya, Jin, Atsushi and Masaru play in each stage of the competition, followed by their reactions to each other’s performances. We are even treated to a long Gothic story involving revenge and twins separated at birth that Masaru imagines as he plays a Lizst sonata. And they all have what can only be described as out-of-body experiences as they play, flying among the stars and seeing visions.

This was all heady stuff, and after a while it reminded me of a hot scented bath—relaxing at first but leaving you dizzy and off balance if you stay in too long. It left me wanting an astringent tonic. But given that a book about a piano tuner won the 153rd Naoki Prize in 2015, it seems that Japanese readers are craving something as distinct from the daily news as they can get. This is very understandable, as the top news stories in Japan this week have been about the emperor’s abdication, the deteriorating relationship between the US and Russia, and the possibility that North Korea is preparing its sixth nuclear test. In that sense, this book reminds us of what remains after the panel of experts has submitted its report, the foreign diplomatic missions are completed, and the games of brinkmanship subside.

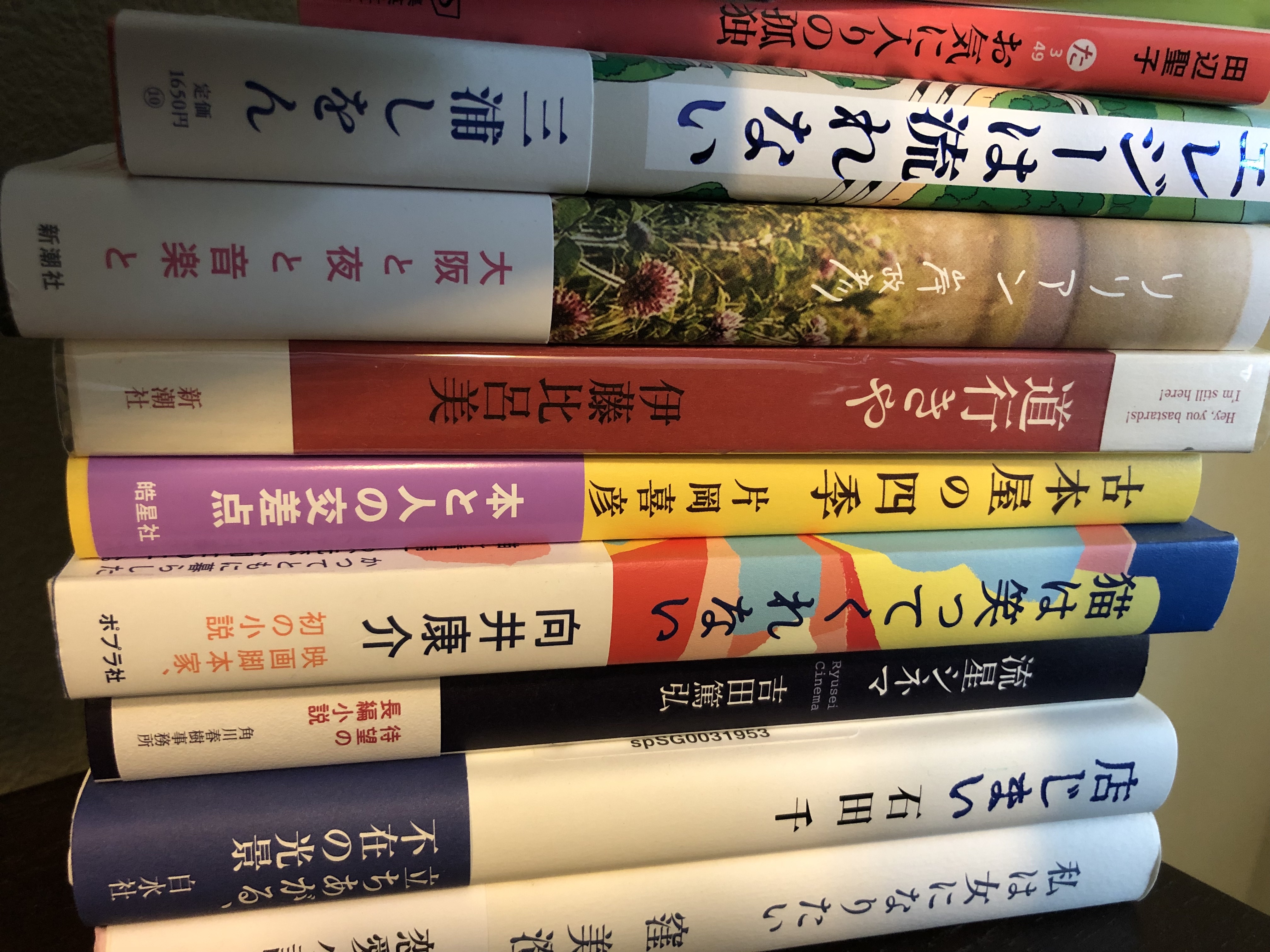

『i』、西加奈子(著)、ポプラ社

『i』、西加奈子(著)、ポプラ社 『暗幕のゲルニカ』、原田マハ(著)、新潮社

『暗幕のゲルニカ』、原田マハ(著)、新潮社 『桜風堂ものがたり』、村山早紀(著)、PHP研究所

『桜風堂ものがたり』、村山早紀(著)、PHP研究所 『コーヒーが冷めないうちに』、川口俊和(著)、サンマーク出版

『コーヒーが冷めないうちに』、川口俊和(著)、サンマーク出版 『コンビニ人間』、村田沙耶香(著)、文藝春秋

『コンビニ人間』、村田沙耶香(著)、文藝春秋 『ツバキ文具店』、小川糸(著)、幻冬舎

『ツバキ文具店』、小川糸(著)、幻冬舎 『罪の声』、塩田武士(著)、講談社

『罪の声』、塩田武士(著)、講談社 『みかづき』、森絵都(著)、集英社

『みかづき』、森絵都(著)、集英社 『蜜蜂と遠雷』、恩田陸(著)、幻冬舎

『蜜蜂と遠雷』、恩田陸(著)、幻冬舎 『夜行』、森見登美彦(著)、小学館

『夜行』、森見登美彦(著)、小学館

Recent Comments