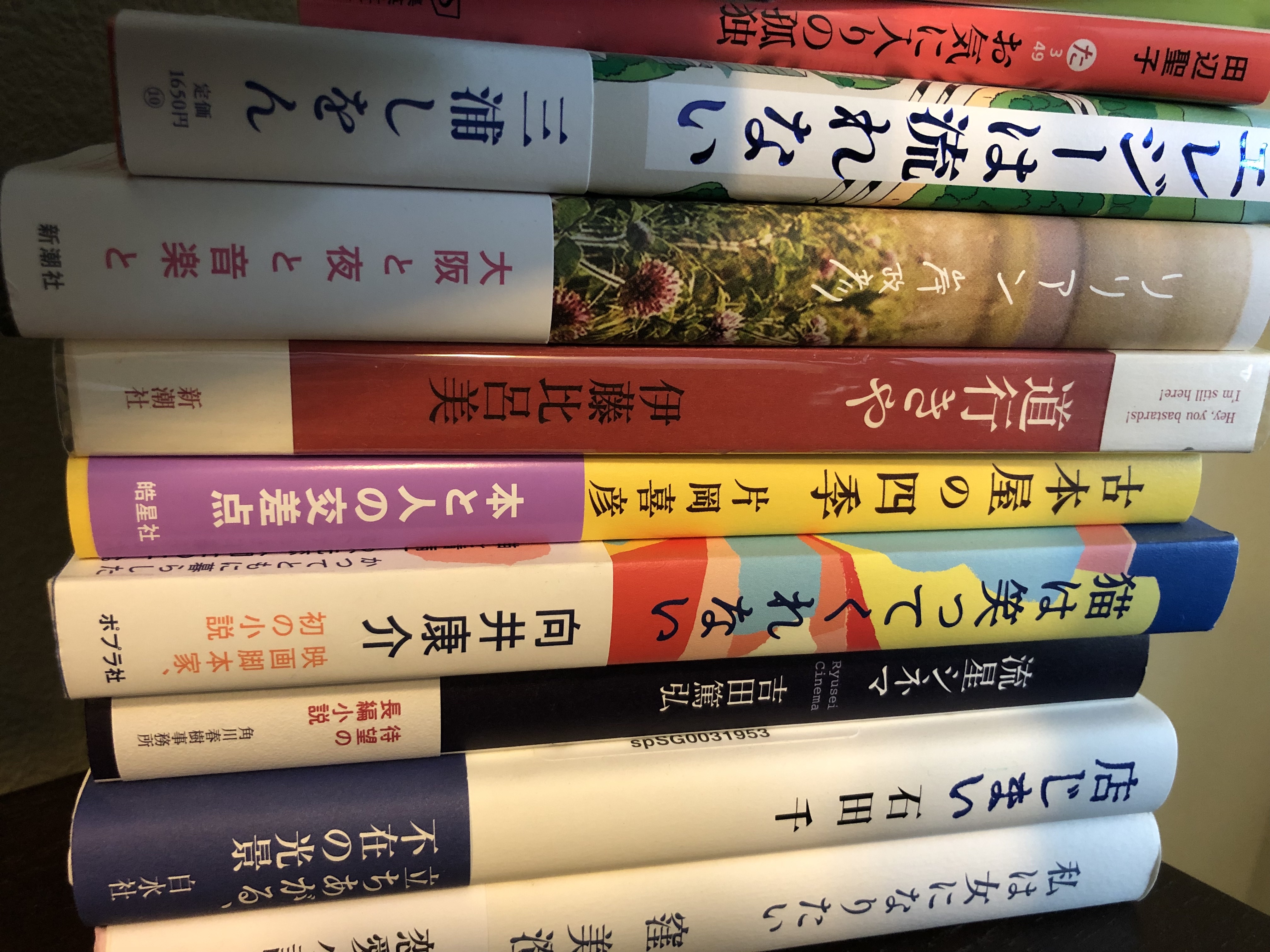

I was in the middle of reading 「熱源」, which won the most recent Naoki Prize, when the coronavirus began spreading, and suddenly reading a book in which the main character watches his community die of the smallpox was beyond me. But although I might reach for a different type of book, I still have to go on reading. Although I wish the circumstances were different, the closure of libraries and bookstores surely makes all of us who have piles of unread books (the very meaning of tsundoku) feel justified. My mother, looking for blankets one day, discovered that my linen closets are used instead as bookshelves, and told me in all seriousness that I needed to see a professional about this “obsession.” But these shelves have certainly preserved my calm over the past few weeks, and in the hope that books might help all of you, I thought I would list the books that I have been reading.

The books we turn to for comfort are different for everyone—some people turn to history, others are re-reading old favorites—and I find that books artificially assigned to this category can be too cloyingly sweet. I want a little bite to my books, even if there is a happy ending. The linked short stories in 「彼女のこんだて帖」(The Women’s Recipe Book) by 角田光代 (Mitsuyo Kakuta) were a little close to this line, but their short length is perfect when your attention is scattered. The stories, which are all accompanied by a recipe, are about people facing difficulties and making things a little better by cooking. A woman who breaks up with her boyfriend recovers her interest in life by learning to cook for one with special ingredients, a widowed man goes to cooking classes to learn how to recreate a dish his wife had made him, a young man learns to make pizza to entice his anorexic sister. The recipes are wide-ranging, from Thai omelets and steamed kabocha to pizza and meatball and tomato stew.

The books we turn to for comfort are different for everyone—some people turn to history, others are re-reading old favorites—and I find that books artificially assigned to this category can be too cloyingly sweet. I want a little bite to my books, even if there is a happy ending. The linked short stories in 「彼女のこんだて帖」(The Women’s Recipe Book) by 角田光代 (Mitsuyo Kakuta) were a little close to this line, but their short length is perfect when your attention is scattered. The stories, which are all accompanied by a recipe, are about people facing difficulties and making things a little better by cooking. A woman who breaks up with her boyfriend recovers her interest in life by learning to cook for one with special ingredients, a widowed man goes to cooking classes to learn how to recreate a dish his wife had made him, a young man learns to make pizza to entice his anorexic sister. The recipes are wide-ranging, from Thai omelets and steamed kabocha to pizza and meatball and tomato stew.

「生きるぼくら」(We are alive) by 原田マハ (Maha Harada) was too far along the Hallmark movie end of the scale for my taste—the kind of book that introduces seemingly insurmountable difficulties one after the other, only for each to be overcome thanks to hard work and the community coming together. Twenty-four year-old Jinsei Akira has been a hiki-komori (shut-in) for four years when his mother suddenly disappears, leaving nothing but a little cash and a bundle of new year’s cards. He finds his grandmother’s card among these and decides to visit her for the first time since he was small. Somehow he is able to not only go outside for the first time in four years, but ask for directions and take a long train ride from Tokyo to his grandmother’s home in the country. Thanks to the kindness of strangers and a few coincidences, he arrives in Tateshina, only to find that his grandmother is suffering from dementia. Jinsei and a newfound half-sister rally around and resolve to take care of their grandmother and her rice fields. I’m glad I read this book if only for the descriptions of her biodynamic method of farming and the slow life they lead, with all the hard work that entails, but serious problems were resolved so quickly and easily that I was left feeling unsatisfied.

「生きるぼくら」(We are alive) by 原田マハ (Maha Harada) was too far along the Hallmark movie end of the scale for my taste—the kind of book that introduces seemingly insurmountable difficulties one after the other, only for each to be overcome thanks to hard work and the community coming together. Twenty-four year-old Jinsei Akira has been a hiki-komori (shut-in) for four years when his mother suddenly disappears, leaving nothing but a little cash and a bundle of new year’s cards. He finds his grandmother’s card among these and decides to visit her for the first time since he was small. Somehow he is able to not only go outside for the first time in four years, but ask for directions and take a long train ride from Tokyo to his grandmother’s home in the country. Thanks to the kindness of strangers and a few coincidences, he arrives in Tateshina, only to find that his grandmother is suffering from dementia. Jinsei and a newfound half-sister rally around and resolve to take care of their grandmother and her rice fields. I’m glad I read this book if only for the descriptions of her biodynamic method of farming and the slow life they lead, with all the hard work that entails, but serious problems were resolved so quickly and easily that I was left feeling unsatisfied.

「天国はまだ遠く」, a short novel by 瀬尾まいこ (Maiko Seo) was more satisfying and complex. With both work and personal relationships going badly, Chizuru decides to commit suicide, and sets off to find an inn in a remote coastal town where she can overdose on sleeping pills. She ends up at an inn that has not had guests in about two years, but the young man who runs it welcomes her anyway. The sleeping pills do no more than knock her out for 36 hours, but the sleep clears her head and Chizuru begins to find an interest in life again. There are no life-changing revelations here, no sudden romances, no easy comfort. The young innkeeper takes her out on a boat and she suffers seasickness; he encourages her to help with the chickens and she is overwhelmed by the terrible smell; she tries to draw the scenery and realizes she has no talent. This more realistic story, complete with prickly characters, felt more satisfying than a novel that tries to wrap everything up with a neat bow.

The novel was made into a film starring Rosa Kato and Yoshimi Tokui.

Being stuck at home without any of the daily interactions that give life variety made me want to experience other people’s lives more, and 「スーパーマーケットでは人生を考えさせられる」 (The supermarket makes me think about life) by 銀色夏生 (Natsuo Giniro) and 「そして私は一人になった」(And then I was alone) by 山本文緒 (Fumio Yamamoto) gave me that. Giniro writes about her nearly daily trips to the supermarket and food stalls in the basement of a nearby department store, describing the dogs tied up outside, the attitudes of the staff and what she cooks and eats. There is nothing profound enough here to merit the title, but it was entertaining in small amounts.

「そして私は一人になった」is novelist Fumio Yamamoto’s diary about living alone for the first time in her life, after going through a divorce. So much has changed since it was published in 1997 that her daily life seems familiar and nostalgic but also inaccessibly distant. She writes about the novelty of a service that allows her to buy a book with just one phone call, about having a “word processor” but being too intimidated to get a modem, and coming home to find paper three meters in length trailing from the fax machine. Yamamoto is the type of person who merely laughs when she gets a phone call in the middle of the night from a young man randomly calling numbers because he once got lucky and got to have “telephone sex” (she does not oblige). And she is very likable—she returns piles of library books to reduce the clutter in her apartment, only to check out just as many all over again, and she wryly notes that, even though she is a writer, she spends far more time reading every day than she does writing. I really enjoyed spending time in her company.

And a little dose of the Moomintrolls, either in Japanese or English, before bed always helps. Tove Jansson began writing the Moomintroll books during WWII “when I was feeling depressed and scared of the bombing and wanted to get away from my gloomy thoughts to something else entirely,” so this seems like the right time to read them. They face dangers and go on adventures, but Moominmamma is always there with comfort, baking a cake even as a comet comes barreling toward Moominvalley.

And a little dose of the Moomintrolls, either in Japanese or English, before bed always helps. Tove Jansson began writing the Moomintroll books during WWII “when I was feeling depressed and scared of the bombing and wanted to get away from my gloomy thoughts to something else entirely,” so this seems like the right time to read them. They face dangers and go on adventures, but Moominmamma is always there with comfort, baking a cake even as a comet comes barreling toward Moominvalley.

The Solitary Castle in the Mirror, by Mizuki Tsujimura

The Solitary Castle in the Mirror, by Mizuki Tsujimura 『キラキラ共和国』、小川糸

『キラキラ共和国』、小川糸 Murderers at the House of the Living Dead, by Masahiro Imamura

Murderers at the House of the Living Dead, by Masahiro Imamura The Fang in the Trick Picture, by Takeshi Shiota

The Fang in the Trick Picture, by Takeshi Shiota “The Sunflower on the Shogi Board,” by Yuko Yuzuki

“The Sunflower on the Shogi Board,” by Yuko Yuzuki The Department Store’s Magic, by Saki Murayama

The Department Store’s Magic, by Saki Murayama Child of the Stars, Natsuko Imamura

Child of the Stars, Natsuko Imamura

Recent Comments