The Way of the Japanese Runner

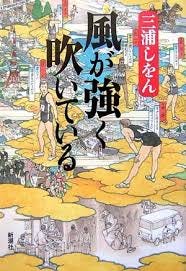

「風が強く吹いている」、三浦しをん、 2006

The Wind Blows Hard, by Shion Miura (no English translation available)

Reading Shion Miura’s books is always an exhilarating experience. I think it’s her sheer enthusiasm for her subjects, which usually involve a deep dive into crafts and occupations that we don’t usually think about much—the painstaking process of compiling dictionaries in 「舟を編む」 (The Great Passage, which I wrote about here), 「神去なあなあ日常」 (”Kamusari Naanaa Nichijo,” here) about the timber industry, the まほろ駅前 series of three books about handymen, and 「仏果を得ず」, a novel about bunraku (traditional Japanese puppet theater), among many others (she is quite prolific). And 「風が強く吹いている」(“The Wind Blows Hard”), a novel about long-distance running no less, definitely falls into this category.

The novel begins as Haiji Kiyose, coming home from the public baths one night, is nearly bowled over by a young man, running all out but breathing as evenly as if he were out for a stroll. He is being chased—ineffectually—by the storekeeper he has just robbed. Haiji gives chase too, not to recover the stolen property, but because he has been looking for someone who can run like this. He realizes that “if there is happiness, beauty and virtue in this world, they are embodied here in this stranger.”

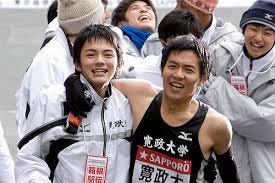

Kakeru and Haiji, played by Kento Hayashi and Keisuke Hoide in the film version of the book

Haiji, a runner himself, finally catches up to the young man, and essentially rescues him. Kakeru (written with the kanji for “run”) Kurahara is starting at Kansei University, but doesn’t have any money left for food (thus the stealing) or rent until his parents send his meager monthly allowance. Haiji offers him refuge in Chikuseiso, a rundown boarding house where he lives with eight others. But Kakeru is right to be suspicious when he hears how low the rent will be (with meals thrown in as well)—Haiji has been looking for one more person to move into Chikuseiso so that he’d have the 10 people needed to form a team for the Hakone ekiden, arguably Japan’s most famous relay marathon.

The origins of the ekiden date back to the Edo period (1603-1868), when couriers running messages between Tokyo and Kyoto would stop for breaks at stations along the route and pass the message on to another courier to carry to the next leg. The name “ekiden” is made up of the characters for “station” and “pass on.” The runners represent this history by wearing a sash over one shoulder that they pass on to the next runner. Ekiden take place throughout the year, run by all age groups, but the Hakone ekiden, run by university students over two days on January 2-3, is probably the most popular (the TV viewing rate was 29.5% for the 2018 ekiden).

All of the Hakone ekiden’s 10 stages are close to a half-marathon in distance, and generally about 30 students of university age run a half-marathon equivalent time of under 63 minutes. For comparison, only one British man ran a half-marathon in less than 63 minutes in all of 2013, and that was the Olympic champion Mo Farah.

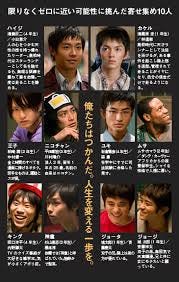

The 10 members of the Chikuseiso team

This is the caliber of runner Haiji’s team will have to compete against, and the first half of the book details Haiji’s efforts to whip his motley crew into shape. The goal of qualifying for the Hakone ekiden seems like a pipe dream at first, given that other than Haiji and Kakeru, none of the residents are runners. Nicotine, who lives up to his nickname, and Oji, a manga fanatic who claims that even a paramecium can run faster than he can, are probably the most difficult cases. However, Haiji maintains that long-distance running is the sport that most rewards effort, with talent having less significance than in other sports. This is really the only hope that the scrappy Chikuseiso residents have against other university teams.

Haiji also has to break down Kakeru’s resistance to competitive running. He had quit his high school team in disgust over the competition, jealousy and intense focus on times. His running team had been bound by hierarchy—the more senior members of the team ate before the younger team members and used the bath first. Now he only wants to run for himself. However, at Chikuseiso, Kakeru can finally breathe. No one cares about birth order or race times, and everyone speaks their minds. Haiji, as coach, simply hands out individualized training plans and offers advice when asked. Kakeru felt like he was watching magic at work—he never imagined such a coaching style could exist.

The second half of the book covers the actual Hakone ekiden. At first I thought 250 pages devoted just to the two days of the race would get tiresome, but Miura uses this as a chance to delve into the background of each of the 10 residents as they run their segment of the race. The course follows part of the old Tokaido road from Tokyo into the mountains to Hakone and then back again the next day. This means that each section is different, challenging the runners in different ways. For example, the first section is flat, but so closely watched by TV crews and crowds of supporters gathered at the starting line that the runner must be able to withstand the psychological pressure. The fifth section is the most intense as runners climb a steep mountain, but the sixth section is mentally challenging as it is primarily downhill and runners must pace themselves. The tenth section is almost flat, but the strong winds blowing between the city skyscrapers often create challenges for runners. Miura tells us in exhaustive (but fascinating) detail how each runner tackles the segment Haiji assigned to them, with flashbacks that add to their back stories and make it clear why Haiji made that choice.

The Way of the Runner by Adharanand Finn (Pegasus Books, 2016) is the perfect accompaniment to The Wind Blows Hard. Finn brought his family to Japan for about a year so that he could explore the story behind statistics showing that Japan has some of the best runners in the world. For example, in 2013, the hundred fastest marathon runners were all from Africa, with the exception of six, and five of these were Japanese. In the same year, no British runner completed a marathon in less than 2 hours and 15 minutes. In the US, 12 men ran under that time, but in Japan, with half the population of the US, 52 Japanese men ran a marathon in under 2:15.

Despite these impressive undergraduate records, by the age of 25 there are few top athletes in Japan and their times are less impressive. Finn attributes this to over-training at an early age, with coaches emphasizing short-term results. He concludes by noting that Japan’s “inward-facing running culture” and its focus on ekiden also limits the success of Japanese runners in international races. Japanese women, who do not face the same pressure as men in ekiden, are more competitive in Olympic marathons because they and their coaches focus more on competing internationally than at home.

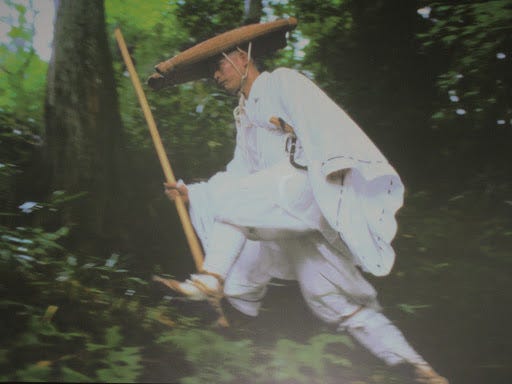

Finn is also fascinated by the marathon monks of Mt. Hiei, Tendai Buddhists who use running as a means of reaching spiritual enlightenment and as a form of meditation. They run the equivalent of a thousand marathons in a thousand days spread over a seven-year period. The monks even carry a rope and knife so that they can take their own lives should they fail to complete the challenge. This trial is so intense (they fast throughout the fifth year) that it is often called a living funeral.

A marathon monk in the handmade straw sandals that they wear for their runs

Finn, who is an avid runner himself, describes running in a way that applies equally to these monks and Miura’s characters: “I often think to myself, just before a race, that I’m about to head down into my well. Down there it is dark, difficult, perhaps even a little bit scary, but it is pure sensation, brute simplicity. Down there, with everything else stripped away, life, the core of life, the breath itself, fills you entirely.”

I think this is what makes Shion Miura’s novel so fascinating—she uses the Hakone ekiden as a literary device that allows her to strip away everything extraneous and get to the core of her characters. As these 10 men run their section of the ekiden, we get to witness these internal struggles, which are far more dramatic than anything bystanders will see as they watch the race. And yes, I even started running again.