Mountain Life

神去なあなあ日常、三浦しをん、徳間書店, 2012

Kamusari Naanaa Nichijo, Shion Miura, Tokuma Shoten, 2012

*Since this post was written, the English translation has been published as The Easy Life in Kamusari, translated by Juliet Winter Carpenter. The sequel is also available as Kamusari Tales Told at Night, also translated by Carpenter.

The title of this book, Kamusari Naanaa Nichijo, presents a perfect case study for the difficulties of translation. Yuki, the narrator, begins the story of his first year in Kamusari by trying to dissect the nuances of なあなあ (naanaa) as it is used in Kamusari. Although it means “take it easy,” and “just relax,” this single word can also be used to say, “the weather today is calm and pleasant.” It is a constant refrain in the speech of people in Kamusari. In fact, the soft “na” is peppered throughout their speech to such an extent that even when they are angry, they still sound relaxed.

Kamusari is a fictional town modeled after 美杉村 (Misugimura), a village nestled against the mountains in 三重県 (Mie Prefecture). Misugimura was merged with nine other towns and is now part of 津市 (Tsushi), an administrative decision that demonstrates the plight of villages like these with dwindling and aging populations.

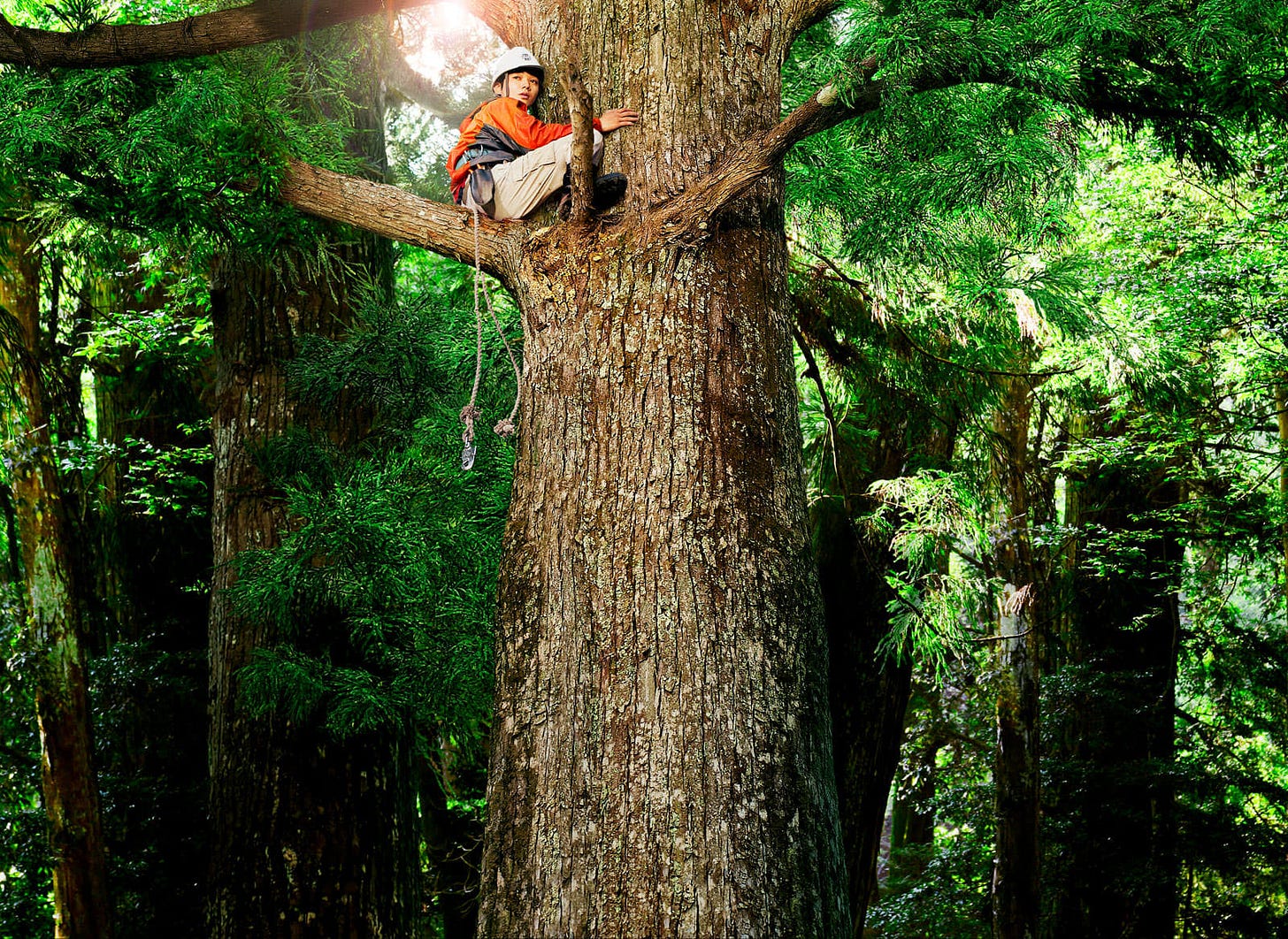

A location shot from the movie of this book, entitled "Wood Job"

A year in Kamusari is enough to show Yuki that the mellow attitude epitomized by “naanaa” has likely emerged alongside the lumber industry, which follows a 100-year cycle. Rushing about will not help the trees grow any faster, and there is nothing to do once it gets dark but sleep anyway, so the pace of life has adjusted to match the slow growth of trees.

It took Yuki months to adjust to life here. Yuki’s mother and high school teacher colluded together to sign him up for a government program aimed at getting fresh blood into dying industries, of which Kamusari’s lumber industry is a prime example. Having graduated high school with no plans for either college or anything other than a part-time job, his mother uses blackmail to force him to go along with the plan and his teacher literally tosses him onto the train. I found this to be unrealistic, and I can’t have been the only one because in the film of the book, it’s the pretty girl on the promotional poster that gets Yuki to join up. However, once the story line had shifted to Kamusari, I was so charmed that I didn’t care what literary device Shion Miura had used to get Yuki there.

After a few weeks of basic training, Yuki is sent to work under Seiichi Nakamura, whose ownership of 1,200 hectares of forests and mountains makes him the head of the village and one of a dying breed of large landowners in Japan. Yuki works in Seiichi’s crew with three other men: Yoki, a young man whose name actually means “axe” and is a kind of genius when it comes to his work in the mountains; Iwao, a 50 year-old man who passes on much of what he knows about the mountains to Yuki; and Saburo, a 74 year-old man who is still a key member of the crew despite his age.

Yuki boards with Yoki, his wife Miki and his grandmother Shige, who for the most part (with a few notable exceptions) sits in a corner like a plump dumpling. I wouldn’t say this book has a plot in a strict sense; instead, Miura builds up the entire world of Kamusari until the reader has soaked up this atmosphere through the pages. It is the little details that create this world, like the 五右衛門風呂(goemonburo) in which Yuki has to learn to bathe and the massive onigiri (rice balls) that Miki makes for their lunch in the mountains. To Yuki, Kamusari is straight out of Japanese folk tales, a place where the threat of the kappa (a river sprite) is enough to keep children from playing in the river without adults.

The kind of 五右衛門風呂 Yuki would have bathed in.

I don’t think I have ever read a book in which the natural environment is such an imposing presence, a character in its own right. The splendor of the night sky makes Yuki dizzy and all his problems seem insignificant. The technicolor display of his first spring in Kamusari takes his breath away and, true to the vocabulary of a teenager, he can only conclude that even computer graphics would be incapable of recreating such brilliant colors. The sound of the trees groaning under the weight of snow makes Yuki so anxious about the fate of the young trees that he can’t sleep.

Yuki in the movie "Wood Job" as he learns to prune the branches of these massive trees

And yet Shion Miura succeeds in avoiding the common pitfalls and tropes too often seen in stories that drop characters into entirely new environments. She doesn’t glorify nature nor does she dwell on the ostracism that Yuki occasionally experiences in this insular village. As if in exchange for the beauty of the seasons, the crew suffers from leaches, ticks and hay fever, and is visited by an earthquake and sudden all-enveloping fogs.

All of the men (and it is all men here) working on the mountains recognize that they are at the mercy of the mountains, and ultimately must rely on the favor of the gods. This means that they avoid killing whenever possible. When Yoki’s dog kills a snake, the crew lays the snake out on a tree stump with a bit of rice, while Saburo pours tea over it and they all bow their heads. This seems strange to Yuki at first, but he gradually senses the strange powers of the mountain for himself. This is a key motif of the story, I think, played out as Yuki begins to participate in the rituals and ceremonies that pacify and honor the mountain and its gods and give the year its structure and rhythm.

An example of the kind of small wooden shrine (hokora) Shion Miura describes.

Although there is certainly some drama in this book—the search for a missing child, a festival that occurs only once every 47 years—I would say that the plot of this book is built on the events that cause Yuki to jettison the vague unease that he is missing out on the life of a typical teenager in a city and instead slide into the slow pace of Kamusari. As he finishes narrating his year, Yuki concludes, “All I know is that Kamusari has never changed and never will.” I cannot help but worry that Japan’s aging population and dying rural industries threaten places like Kamusari, and I’m glad that its atmosphere has been preserved in the pages of this book.

For anyone wanting a further look, there are some beautiful pictures of Misugimura here.

Note on the author: Shion Miura has an impressive list of books to her name, especially considering that she is only 40. The daughter of a classics scholar, her talent was recognized straight out of college and she began writing book reviews. She has won several awards, including the Naoki Prize forまほろ駅前多田便利軒 (The Handymen in Mahoro Town) and the Booksellers Award for 船を編む (The Great Passage), a novel that makes the compilation of a dictionary seem like a grand endeavor. You can read more about Miura and some of her other books here. Unfortunately, none of her novels have been translated into English yet.