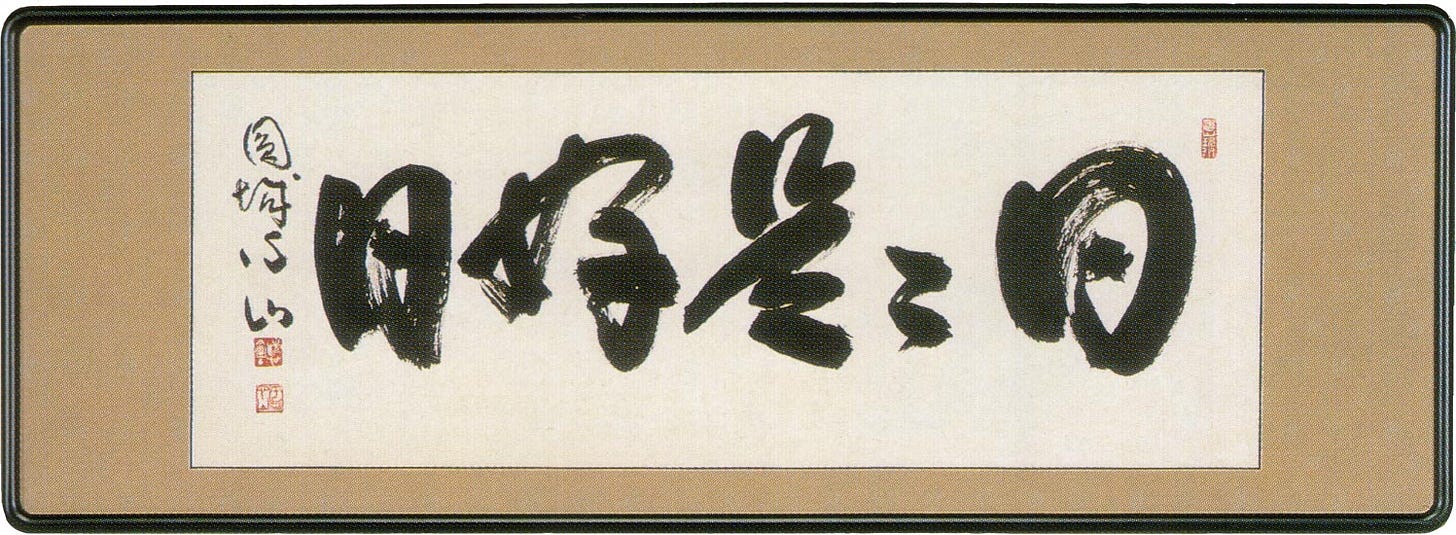

日日是好日 (Every day is a good day)

「日日是好日」 森下典子 (Every day is a good day, by Noriko Morishita)

I have admired Noriko Morishita’s essays for many years, but the quiet tone of her writing and subjects aren’t qualities that usually earn authors a place on bestseller lists. So I was surprised to see that her book of essays on the tea ceremony, 「日日是好日」 (Every day is a good day), had become a bestseller in Japan, 16 years after it was first published. It made more sense when I saw that a film of the book had just been released, starring Kiki Kirin (who died in September 2018, just before the movie was released) and Haru Kurogi.

Noriko began studying the tea ceremony in her third year of college, at her mother’s suggestion. She was reluctant because she saw the tea ceremony and ikebana as something old-fashioned that only girls who believed that searching for a husband was equivalent to a job search did, but she agreed to go with her cousin Michiko. Her first classes were incredibly frustrating for her: the rules about how to walk into the tea room, how to sit, and which way to face seemed like empty formalism, summing up everything she hated about Japanese traditions. Noriko watched her teacher, Mrs. Takeda, take the fukusa (silk cloth) between her fingers, run it along the rim of the teacup and turn the cup three times, and then trace the character ゆ on the bottom of the cup, but when she asked why this was done, Mrs. Takeda said it didn’t matter and there was no need for a reason. And even once Noriko did become more interested, Mrs. Takeda wouldn’t let her take notes because the motions had to become part of her physical memory. For months she moved like a marionette under Mrs. Takeda’s step-by-step instructions. She had to trust in the process until finally, one day her hands moved on their own and each of the steps flowed together.

These essays cover Noriko’s life from her 20s through her 40s. The tea ceremony is a constant in her life, getting her through a broken engagement just months before her wedding, doubts about her chosen career, and her father’s death. The tea ceremony’s ritualized celebration of the changing seasons became a way for her to encourage oneself and get through the more difficult seasons of her own life. Japan’s 24 sub-seasons—from 節分 (the traditional end of winter) and on to 立春 (the first day of spring), then 雨水 (rainwater), 啓蟄 (insects awaken) and so on until the cycle ends with大寒 (greater cold)—are all recognized with a change in the flowers and scroll hung in the tokonoma (a recessed space in a room). On お月見 (moon viewing day), the scroll simply showed a circle. During the rainy season, the scroll said 聴雨, “listen to the rain.” Even the sweets mirrored the seasons. Mrs. Takeda travelled to long-established shops all over the country to buy the sweets she used in her tea ceremony classes. In mid-December, they had yellow yuzu-flavored manju. In January, they had a dried sweet that looked like a flat white square of sugar but dissolved like snow on the tongue.

The tea ceremony is aligned to time both on the smaller scale of the seasons within a year and on the larger scale of the zodiac. Noriko noticed that the cups used in the first and last tea ceremonies of the new year are decorated with the zodiac animal for that year, and then they are put away again until their turn comes around again in 11 years. The tea ceremony continues to rotate through the 12 zodiac cycles without end, but a human life is only six or seven cycles, which gave Noriko a profound sense of the brevity of her life.

The changing of the seasons, and the way they are reflected in the tea ceremony, also forced Noriko to let go of thoughts and habits she had clung to. Every November, part of the tatami flooring is lifted to reveal a sunken hearth in which the kama (iron kettle) is placed for the tea ceremony. November is 立冬 (the beginning of winter) in the old calendar, representing the new year for tea ceremony practitioners. The hearth becomes the point of reference, which changes the placement of the utensils. In May, which is 立夏 (the beginning of summer) in the old calendar, the hearth is covered over again and the “summer tea ceremony” starts again. These changes confused Noriko at first, but Mrs. Takeda told her, “Do what is in front of you right now. Focus your emotions on ‘now.’”

This was particularly hard for Noriko when she felt like her own life was standing still as her friends all seemed to be marrying, trying to balance work with children, even moving overseas. She couldn’t seem to feel anything but impatience at her tea classes—she felt like she should be doing something, not just sitting. But there were moments when she just let herself enjoy the quiet, the ritual, and the mossy taste of the tea. Her head would empty and she would think of nothing, in a peace deeper than sleep. It reminded her of the way warriors had to take off their swords to come through the small entrance of the tea room, so that the warrior would be relieved of his role for as long as he was in the room and could just be a human being again.

Noriko eventually realized, over the decades of her practice, that the tea ceremony is a way to experience the aesthetics and philosophy behind the way the Japanese live, in line with the rhythm of the seasons and through one’s own physical experiences. Even if Mrs. Takeda had explained all of this on the first day, she wouldn’t have been capable of understanding. Following the formal steps of the tea ceremony by relying on her body’s own memory of steps emptied her head so that it became a form of meditation, allowing Noriko—for fleeting moments at least—to just be.

The Tea Ceremony’s Lessons on How to be Happy, according to Noriko

1. Recognize that you know nothing

2. Do not think with your head

3. Focus on the present

4. Look with all of your senses

5. Observe the real thing

6. Savor the seasons

7. Connect to nature with all five senses

8. Live in the present moment

9. Trust your body to nature and let time pass

10. Take each moment as it is

11. Parting is inevitable

12. Tune in to oneself

13. On rainy days, listen to the rain

14. Wait for growth

15. Take the long view but live in the present

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=100&v=ojfkRsr_xMg