Breath of Words

ツバキ文具店、小川糸、幻冬舎、2016 Tsubaki Stationery Store, by Ito Ogawa, Gentosha, 2016 Hatoko lives in a traditional Japanese house in Kamakura that does double-duty as a stationery store (the Tsubaki Bunguten of the title). She was raised by her grandmother in this house, but escaped her high expectations and rigidity as soon as she could. When the novel begins, Hatoko has returned from several years living abroad to take over the family business after her grandmother’s death, which includes work as a scribe in addition to running the stationery store. Hatoko’s grandmother had taught her how to write using ink and brush as soon as she was old enough to hold the brush, starting her off with circles, zigzags and helixes. When other children were playing after school, Hatoko was at home learning calligraphy under her grandmother’s strict tutelage.

Ito Ogawa, the author, working at her home in Kamakura Source: Croissant magazine

Hatoko writes a letter pretending to be the deceased husband of a woman with dementia who still waits for his letters; she captures his handwriting perfectly. Although writing letters for other people had seemed deceitful when she was younger, Hatoko gradually realizes that scribes are essentially writing letters for people who cannot express their feelings in words themselves—her grandmother described it as being a 影武者 (kagemusha), a body double or someone working behind the scenes. Now she writes goodbye letters, letters encouraging people unable to find jobs, apologies for disgraceful behavior when drunk—words that are hard to say face to face. Over the course of this book, she writes a letter announcing a divorce that also manages to convey the couple’s happiness over 15 years of marriage, a condolence letter after the death of a friend’s monkey, a letter refusing to loan money, a birthday card to the mother-in-law of a woman with horrible handwriting, and a letter to a woman with dementia purporting to be from her long-dead husband.

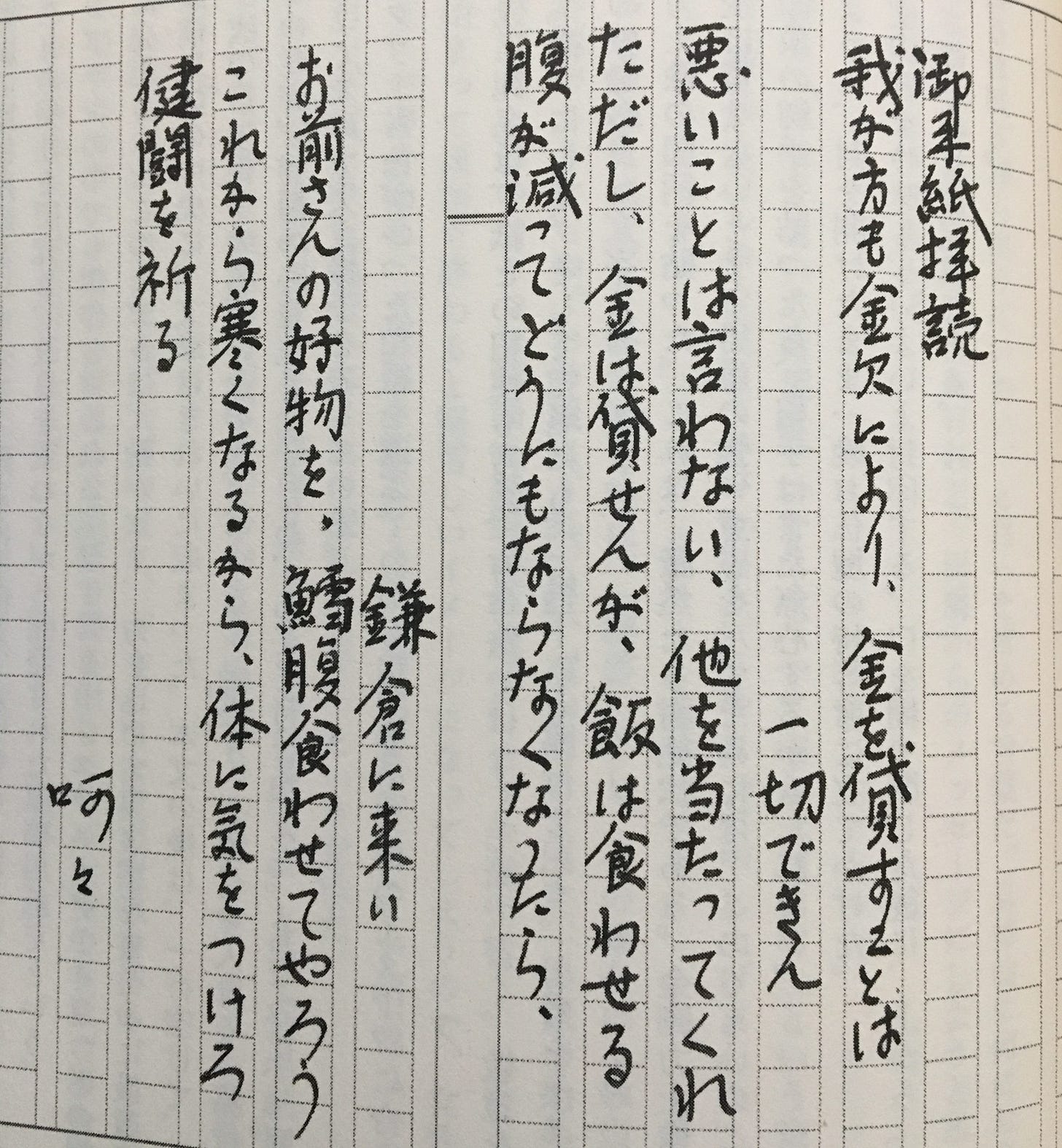

A letter Hatoko writes for a man refusing to loan money; the handwriting captures his brash personality Hatoko tries to convey a person’s personality in the letters she writes, using handwriting that fits them. She is scrupulous about every last detail of writing letters, choosing the perfect ink, paper and stamp. When writing a letter to break off a relationship between two friends that has become poisonous, she searches for paper that can’t be easily torn and settles on parchment. For the letter announcing the break-up of a 15-year marriage, she finds a stamp issued the year the couple were married. Hatoko lives her life at a deliberate, slow pace that belies her young age. In the morning, she dresses and washes before putting water on for tea. While she waits for the water to boil, she sweeps the floors and wipes them down with a damp cloth. And while her tea steeps, she polishes the floors. After drinking her tea, she puts fresh water by the 文塚 (fumizuka), a burial mound where poems and other manuscripts are buried to memorialize or commemorate them.

The fumizuka Hatoko cares for commemorates letters. From the third day of the new year, mail begins to pour in from all over Japan and even overseas from people who can’t bear to throw away letters themselves. Many of these letters are love letters that the recipients are unable to give up until just before they marry someone else. Some people even send all the letters they receive over the course of the year. On February 3, according to the lunar calendar, she burns the letters and preserves the ashes. This aligns with her family’s belief that letters are essentially an offshoot of the writer, the words infused with their breath. (Lest this sound too solemn an occasion, I should mention that a friend joined her for this winter bonfire and they roasted potatoes, Camembert cheese, rice balls and French bread in the embers.) The book is divided into the four seasons, and as the reader moves from summer to spring, Hatoko seems to be taking on the mantle of scribe and the traditions of her home. I could say that she is “coming to terms with” a childhood lacking in affection, but this phrase is too trite after overuse in misery lit and doesn’t convey the quiet of this novel. There is none of the navel-gazing that I often find in contemporary American novels. Her conflicts (even that word seems overblown) lie below the surface, revealed briefly when, for example, an old friend brings her a bag of the seven spring herbs used to make rice porridge on January 7. Growing up, Hatoko’s grandmother always soaked these plants overnight on January 6 and made Hatoko dip her nails in the water the next morning before cutting them for the first time in the new year in the belief that this would prevent colds all year. She realises that she hasn't observed this custom since her rebellious period as a teenager, but now that she’s back she gradually returns to many of these traditions.

Hatoko finally finds her own handwriting in this letter she writes to a little girl who lives next door. As a scribe, Hatoko is very skilled at imitating other people’s handwriting and writing in a script suited to the letter’s subject, and yet she doesn’t know what her own handwriting might look like. She had never written a letter to her grandmother nor received a letter from her. Her grandmother did have a writing style all her own, however, and that’s why Hatoko has never taken down the scrap of paper hanging in the kitchen on which her grandmother had written a proverb: Eat food to match the seasons—bitter foods in the spring, vinegary foods in the summer, pungent and spicy foods in the autumn, and oily and fatty foods in the winter. At the end of the book (and I don’t think this gives anything away—after all, as with any good book, the end is not the point), Hatoko takes down the yellowed paper and rewrites it in her own handwriting, for herself. I was initially drawn to this book because it was about a stationery store, which is almost as good a setting as a coffee shop or bookstore (at the moment I’m reading a book set in a shop that makes onigiri, or rice balls). If anyone else loves Japanese stationery, you might be interested in this news story about a stationery store that only opens at night called Punpukudo (the article is only in Japanese but the pictures are worth a look). The store, opened by a woman who has loved collecting pencils with different designs since she was little, is open only 5-10pm on weekdays.

Punpukudo, a stationery store in Ichikawa, Chiba prefecture

Source: Asahi Shimbun