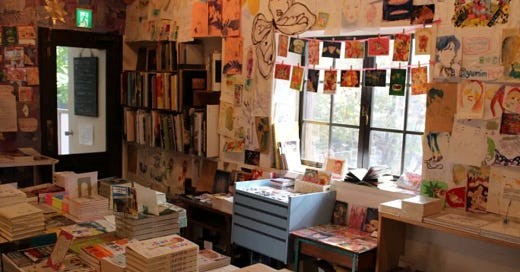

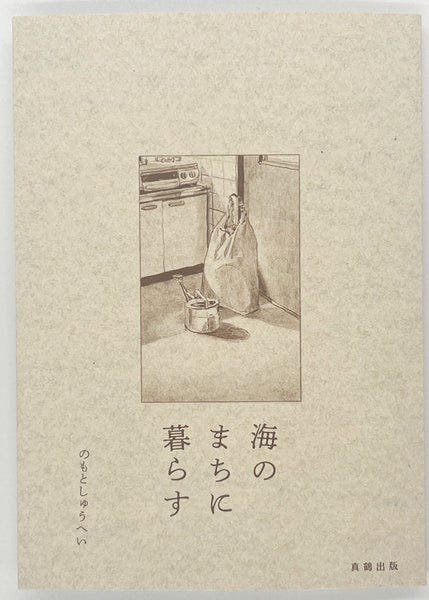

Reams of paper have been devoted to extolling the virtues of—in fact, the need for—independent bookstores. I’ve always been a true believer myself, but the difference really hit home during a typhoon last August, when I found the tiny bookstore 百年 (Hundred Years) in the back streets of Kichijoji. It primarily sells used books, but also has a few tables of carefully-chosen books from independent publishers. One of these was 「海のまちに暮らす」 (Living In a Seaside Town) by のもとしゅうへい (Shuhei Nomoto) and published by 真鶴出版 (Manazuru Shuppan) in 2024. I couldn’t have found this in any of the big bookstores, and don’t bother looking for it on Amazon. The same was true of the other books I found there, all of which ended up being connected in the way they question how we live and gently suggest alternative perspectives.

In 「海のまちに暮らす」, Nomoto describes how he took a leave of absence from his art school in 2021 and retreated to Manazuru, a seaside town he had heard about from a professor. Surrounded by resort areas like Hakone and Atami, Manazuru had avoided development and still had a down-to-earth feel. He found a house four times as big as his one-room apartment in Tokyo at the same rent, and spent his days reading, drawing and walking when not working at the local library and Manazuru Publishing’s guesthouse. In the process, Nomoto learned how to get along with himself, as he puts it, gathering little pieces of wisdom as he went through his slow daily routine —nothing earthshattering, just how to clean toilets and make beds at the guesthouse, how to get up at 5am to work in his vegetable plot, how to protect time for reading and writing. He describes this process as similar to picking up clothes from the floor. Maybe it was because I was in a shabby rented room overrun by ants crawling on the floor and walls, with a typhoon raging outside, but I wanted to pick up and move to Manazuru at once.

I couldn’t go that far (at least, not yet—I’m still hoping), but I was able to visit Manazuru, which is only about an hour and a half by train from Tokyo Station. On the train, I read 「百年の一日」(One Day in a Hundred Years), the journal that 樽本樹廣 (Mikihiro Tarumoto), the owner of 百年, wrote over the course of a year from July 30, 2006, when he first opened the store. Tarumoto does not romanticize the life of a bookseller, pointing out that it is essentially physical labor that robs you of time to actually read books and results in chronic back pain. In the first few years his salary was never more than 130,000 yen per month, less than he paid his part-time employee (luckily, his situation his improved—in 2019, he said in an interview that he had recently bought a house and wanted everyone to know that even booksellers can get married, raise kids and qualify for loans).

Source: マネーフォワード

He notes that there are many people from his generation that run used book stores, which he attributes in part to the fact that they are the “ice age” generation, the cadre that graduated in roughly 1994-2004 into a struggling economy that couldn’t offer enough steady jobs. Rather than continue in part-time jobs, they decided to try running bookstores, something that is relatively inexpensive to start (by joining the used book association, you can participate in auctions and stock your shelves; the cost of joining was 600,000 yen in 2023).

Similarly, in 「小さな泊まれる出版社」 (Small Publisher and Guest House), Tomomi Kishi writes about how she and her husband, Shun Kawaguchi, came to start Manazuru Publishing. Growing up, Kishi lived in an apartment building where kids of all ages ran in and out of each other’s houses, but she never found this sense of community again once her family moved to the suburbs. When she got to college, every class she took, regardless of the subject, made her think that Japanese society couldn’t go on as it was. She was convinced that a society in which 30,000 people commit suicide every year has serious structural problems. Kishi had no interest in looking for a job, but there was no one in her orbit who did anything but work for companies. She ended up working as a Japanese teacher overseas for many years, and when she came back, she and her husband started their combination guest house and publishing company in Manazuru.

One reason they chose Manazuru was because it had devised a design code laying out its own standards for beauty in 1993. Covering any building constructed there, it was meant to limit development after the so-called resort law, which encouraged the development of large resorts, particularly outside of the major cities, went into effect in 1987. The standards read like poetry, putting into words qualities that most people appreciated sub-consciously but hadn’t bothered to identify before: quiet back streets, living roofs, views of the ocean from stairways, design aligned with sloping surfaces, natural and living building materials, and roads that are so narrow that only people can use them.

Kishi writes that these qualities may help protect Manazuru from the waves of capitalism that extend beyond large cities now, promising convenience in the form of stores with long opening hours and consistent quality standards. But in reality, it has resulted in higher land prices so that small stores—bookstores like 百年 , for example—can no longer survive or even open in the first place, and the unique nature of a small town in which many tiny shops jostle shoulders is lost. Anything deemed “unproductive” (such as roads that have room only for people, not cars) is shut out under capitalism. In its place, Kishi suggests a philosophy centered on daily life rather than profit. Small towns are inconvenient, but they have blank space in which people can experiment, just as Nomoto did. Land prices are cheap outside of the big cities, which makes it possible for people without much capital to do the work that inspires them.

In 「村上朝日堂」 (Murakami Asahido), Haruki Murakami wrote that when he was young, people who had no money but didn’t want to get a job could start their own business on the basis of a good idea. Murakami himself opened a jazz bar in 1974, when he was still a student in Waseda’s literature department. He had 5 million yen in capital (about USD33,328 at today’s conversion rate), some borrowed from his parents and some from savings. This was enough, in those days, to rent a pretty large space in a good location in the Kokubunji area of Tokyo. But it has become more difficult to take on this kind of challenge now that land and construction prices have gone up so much. Writing back in 1987, Murakami notes that he is particularly worried about stultifying social conditions—the same conditions that Kishi and Tarumoto bucked—because people who, like him, didn’t want to find a 9-5 job but had no money no longer seemed to have other options. And as all three of the books I found at 百年show, the more alternative paths a society can provide, the healthier that society can be.

If you can make it to Manazuru yourself, I recommend trying one of the walks introduced here (only in Japanese). The three-hour walk is lovely and brings you right down to the ocean.

And you can stay at Manazuru Publishing yourself (overseas guests are very welcome), something I hope to do myself soon.

You're back! I missed your blog.