「むらさきのスカートの女」、今村夏子

Purple Skirt Lady, by Natsuko Imamura

*Since this post was written, the English translation has been published as The Woman in the Purple Skirt, translated by Lucy North.

After being nominated three times, Nastuko Imamura won the 161st Akutagawa Prize for 「むらさきのスカートの女」(Purple Skirt Lady). Sometimes Akutagawa Prize-winning books seem to take themselves too seriously, but that is definitely not true of this playful (but creepy) novel. It can be read in a few hours, but I’m still thinking about it, trying to figure out what kind of game Imamura was playing.

This novel is narrated in the first person, leaving the reader with no choice but to rely on what the narrator chooses to tell us. And our footing as readers feels increasingly unstable. Initially, we know next to nothing about the narrator, other than that she is essentially stalking this woman that “everyone knows” as the Purple Skirt Lady (the narrator would like to be known as the “Yellow Cardigan Lady” but it hasn’t caught on yet…). And at first, I watched the narrator stalking the Purple Skirt Lady, but by the end, I was watching the narrator.

The narrator keeps track of how often the Purple Skirt Lady changes jobs, what stores she frequents, and exactly how she eats her cream-filled roll. We are told that a bench in the park is reserved for the exclusive use of the Purple Skirt Lady, and we have no reason to doubt this (but doubts creep in later). The narrator seems quite protective of the Purple Skirt Lady. She chases away people who have the nerve to sit on her bench, and when the narrator notices that she has been out of work for quite a while, compared to her previous work history, begins leaving job information magazines on her park bench. The narrator even helpfully circles the job she wants her to apply for. It takes quite a while before the Purple Skirt Lady gets the message and finally applies for the job cleaning at a hotel where, not coincidentally, the narrator works. The narrator even hangs a bag with shampoo samples on her apartment door to make sure that, for once, the Purple Skirt Lady washes her unkempt hair before the interview.

I had assumed that the Purple Skirt Lady was quite odd—after all, children in the park play a game in which they tap her on the shoulder and run away—but she adapts so quickly to the work culture that I began questioning the narrator instead. Her colleagues find the Purple Skirt Lady charming and quick to learn, and her superiors at the hotel think she shows promise, even talking of promotions. She even has an affair with her boss.

There is no authorial voice to give us a neutral view of events, although the narrator reports conversations and scenes that are hard to imagine she could have witnessed without either invisibility or some other form of magic. The Purple Skirt Lady never even notices her until the very end. I was alternately scared about where this was going and amused—a very unsettling reading experience. The narrator depicts all the comforting details of daily life—bus schedules, bakeries, parks and children, shopping for daily necessities—but they are all reflected through the filter of her obsession.

The narrator’s most unhinged behavior makes for the funniest scenes in the book. She is particularly impressed with the Purple Skirt Lady’s effortless stride through crowds of people, and in an effort to break her stride that goes completely wrong, the narrator crashes into a glass counter. The damages she then has to pay put her in such straitened circumstances that she can no longer pay her rent and other bills. In another ridiculous scene, the narrator is so desperate for the Purple Skirt Lady to notice her that she grabs her nose in a crowded bus, and is then extremely miffed when she doesn’t seem to even notice. Instead, just as the narrator is about to grab her nose again, the Purple Skirt Lady announces that she has been molested by a man on the bus, angry passengers secure the offender, and the bus driver makes an emergency stop at the police station.

This novel has some similarities to Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman that might help its chances of publication in English translation. Just as Murata made me question socially-ingrained assumptions, the supposedly “normal” employees at the hotel at which both the narrator and the Purple Skirt Lady work bully other new employees, steal from the hotel as if they deserve it, and are so quick to turn on the Purple Skirt Lady that they were easily the most despicable characters in the book. And the narrator, like Keiko in Convenience Store Woman, is unintentionally funny in her inability to figure out how to fit in. However, Imamura’s novel feels darker. There are plenty of funny scenes that relax the tension for a while, but toward the end, events seem to take a very dark turn until, once again, Imamura showed that we can’t assume anything while we are in her hands.

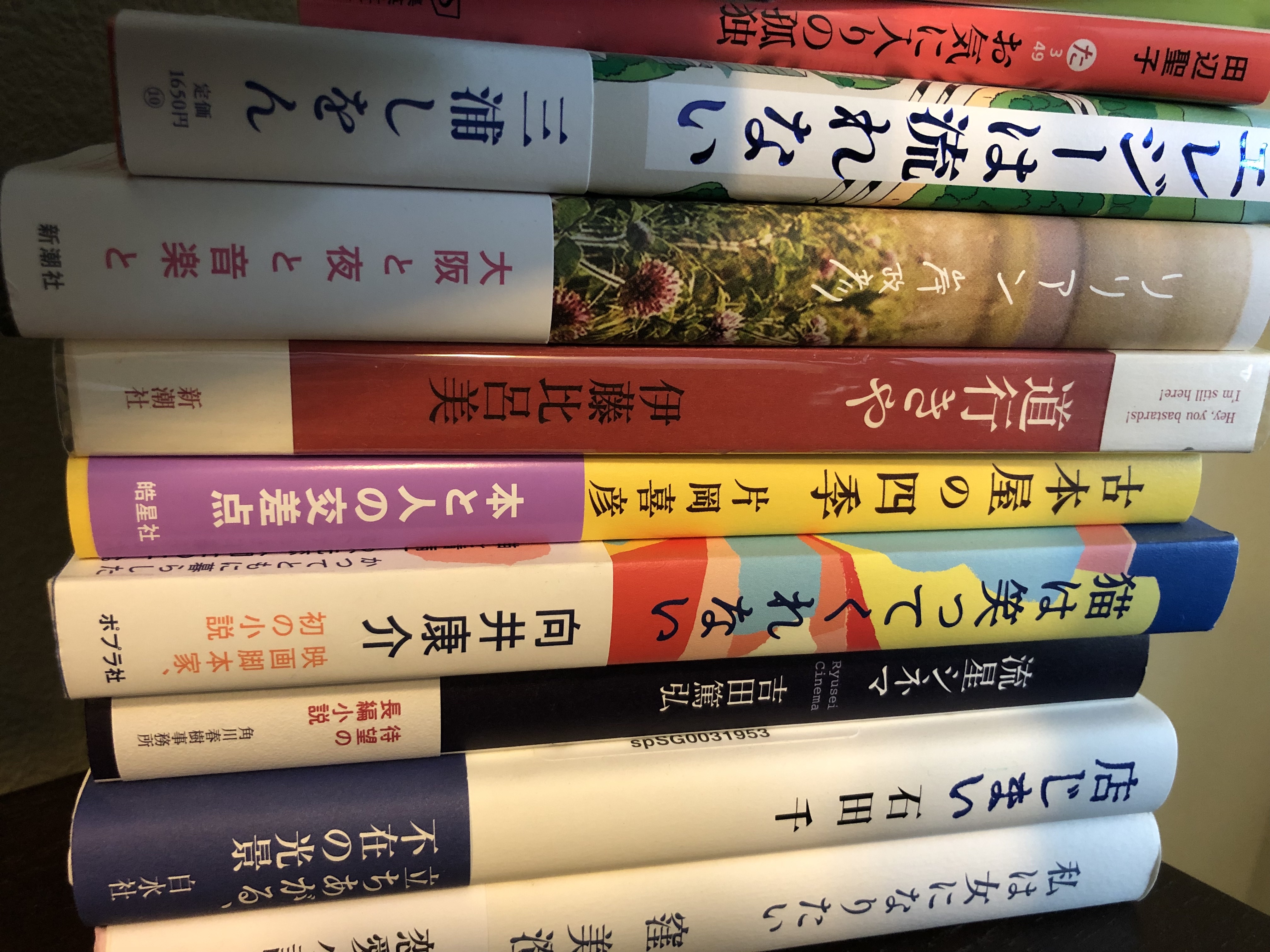

The Solitary Castle in the Mirror, by Mizuki Tsujimura

The Solitary Castle in the Mirror, by Mizuki Tsujimura 『キラキラ共和国』、小川糸

『キラキラ共和国』、小川糸 Murderers at the House of the Living Dead, by Masahiro Imamura

Murderers at the House of the Living Dead, by Masahiro Imamura The Fang in the Trick Picture, by Takeshi Shiota

The Fang in the Trick Picture, by Takeshi Shiota “The Sunflower on the Shogi Board,” by Yuko Yuzuki

“The Sunflower on the Shogi Board,” by Yuko Yuzuki The Department Store’s Magic, by Saki Murayama

The Department Store’s Magic, by Saki Murayama Child of the Stars, Natsuko Imamura

Child of the Stars, Natsuko Imamura

Recent Comments