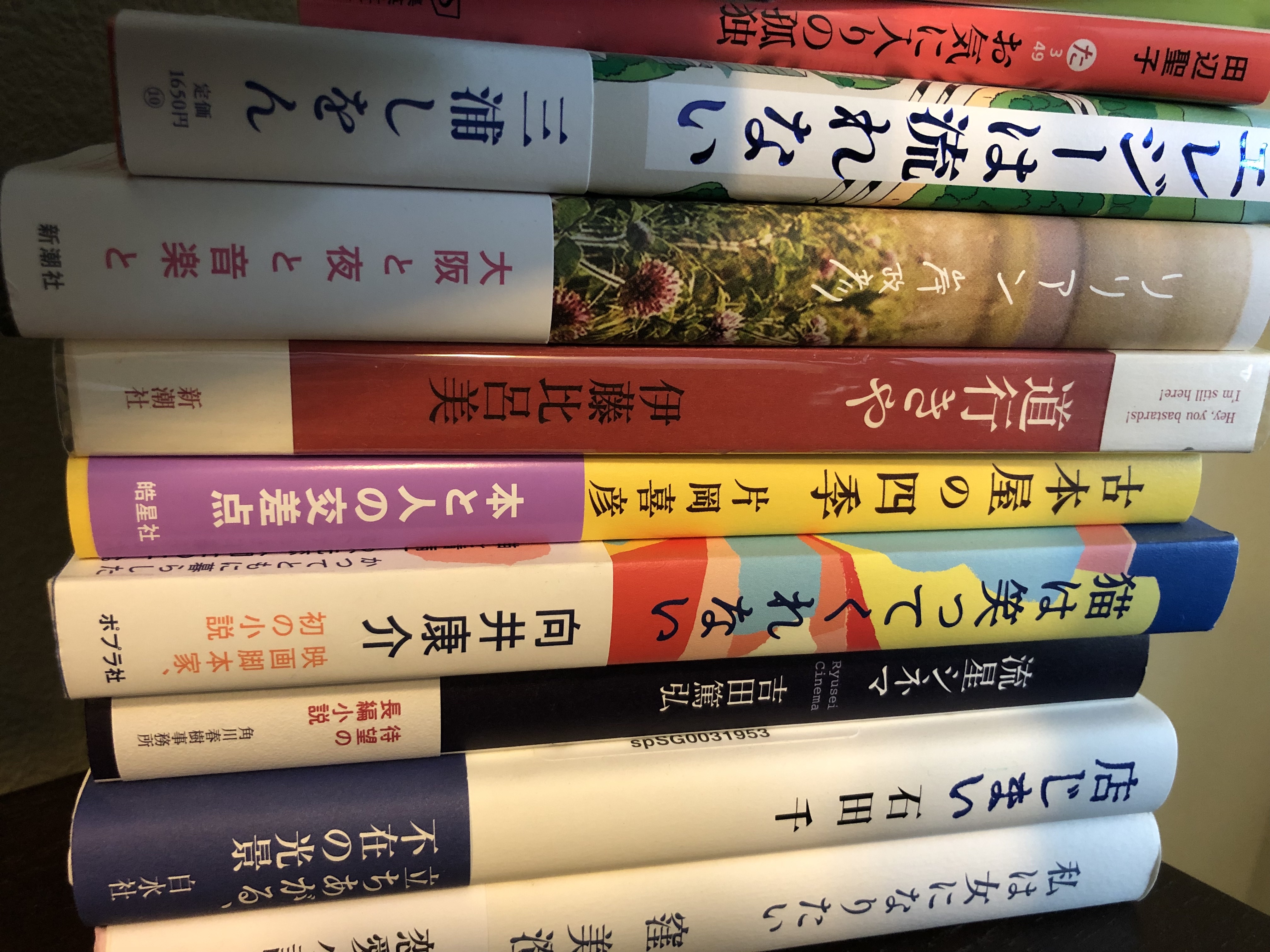

舟を編む、三浦しをん、光文社、2011

舟を編む、三浦しをん、光文社、2011

The Great Passage, by Shion Miura, Kobunsha, 2011

*Since this post was written, the English translation has been published as The Great Passage, translated by the brilliant Juliet Winter Carpenter.

The Great Passage is an unabashedly romantic book—romantic in the sense that Shion Miura is telling a story about lofty goals and a pursuit that is almost heroic in its aspirations.

An underfunded and understaffed department at Genbu Publishing is compiling a dictionary covering 230,000 words—a project that has subsumed the lives of Professor Matsumoto and Kohei Araki. When the book begins, Araki is looking for his successor so he can take time off to care for his ailing wife. Told that there is a strange man in the sales department with an advanced degree in linguistics, Araki searches out Mitsuya Majime (whose last name means “serious”) and, after testing him by asking him to define the direction “right,” rescues him from the sales department.

Majime joins the small team working on the dictionary they have named 大渡海 (Daitokai, literally “great passage across the ocean”), reflecting their vision of dictionaries as boats that cross the ocean of words. Araki explains to Majime that people sail on this boat to gather the small specks of light floating on the  surface of the dark ocean, searching for the word that will most accurately and faithfully convey their thoughts to other people. Without dictionaries, people would just stand, wordless, in front of the ocean’s wide expanse.

surface of the dark ocean, searching for the word that will most accurately and faithfully convey their thoughts to other people. Without dictionaries, people would just stand, wordless, in front of the ocean’s wide expanse.

Surrounded by sympathetic colleagues on the same wavelength and faced by an intriguing young woman in his boarding house, for the first time Majime finds that he wants to find the right words to convey his thoughts. He has no friends and has always been seen as eccentric in both his school life and work life. He found refuge from this sense of isolation in books, which in turn fed his interest in linguistics and led him to the dictionary department.

Majime (played by Ryuhei Matsuda) with his cat, Tora

Asked about his hobbies at his welcome dinner, Majime replies that if he had to pick something, it would be watching people get on the escalator. Greeted by a deafening silence, Majime explains that when he gets off the train, he purposely walks slowly and lets the other passengers overtake him. They all rush to the escalator, but there is no confusion or shoving. As if someone is controlling their movements, they sort themselves into two lines and board the escalator in order. People on the left stand still, and people on the right walk up—a beautiful sight that makes Majime forget the crowds around him. Matsumoto and Araki  know exactly what he means—clearly Majime is suited to the work of compiling dictionaries. Just like commuters sorting themselves into queues, words are collected, classified, put into groups and organized in order on the pages of a dictionary.

know exactly what he means—clearly Majime is suited to the work of compiling dictionaries. Just like commuters sorting themselves into queues, words are collected, classified, put into groups and organized in order on the pages of a dictionary.

This is the kind of episode that makes Masashi Nishioka, another member of the department who is Majime’s complete opposite, feel out of place. He has no talent for dictionary work, but earns his keep by collecting the gossip that leads Araki to Majime and gives them warnings of impending funding cuts to the department, and using a combination of flattery and threats to get academics to contribute dictionary entries. Nishioka had never met anyone like Majime, Araki and Matsumoto. Professor Matsumoto’s bag is always packed full of old books. On his way to work, he goes to the secondhand bookstores in Jimbocho and buys first editions of novels to search for new words, their first usages, and example sentences for the dictionary. When he eats lunch, Araki has to make sure Matsumoto uses his chopsticks to eat and not his pencil because he becomes so absorbed in writing down the words he hears on TV that he is liable to eat his noodles with his pencil.

Watching them so absorbed in their work made him feel that his life was lacking in passion. How do you  find a goal that is worth such single-minded dedication? Nishioka watches Majime and Matsumoto spend their own money on reference materials and become so absorbed in their research that they miss the last train. Although he doesn’t understand this devotion, he likes being a part of this work, almost as if hoping that a bit of their enthusiasm would rub off on him.

find a goal that is worth such single-minded dedication? Nishioka watches Majime and Matsumoto spend their own money on reference materials and become so absorbed in their research that they miss the last train. Although he doesn’t understand this devotion, he likes being a part of this work, almost as if hoping that a bit of their enthusiasm would rub off on him.

After initial resistance, Midori Kishibe also finds her own way into this world. Joining the department over 10 years after Majime first joined the department, she initially dismisses Majime as a bumbling eccentric and the dictionary as a worthless obsession. She had been working for a department that published a

Rows and rows of cards with words, their meanings and usage inscribed

fashion magazine for young woman when she was transferred to this dusty department located in a ramshackle outbuilding. But despite her skepticism and even derision, she is no more immune to the lure of this grand endeavor than Nishioka was. She becomes fascinated with the process of developing paper for this dictionary. Paper is being developed especially for this dictionary, as it must be thin enough to ensure that the dictionary is not too bulky, but not so flimsy that the words on the opposite side of the paper seep through. When flipping through the dictionary, the pages should turn like sand through your fingers. The paper should have a warmth to it, and Majime insists that it have a slight stickiness so that the user’s fingertips can gain purchase on the pages. Every last detail is considered.

Majime’s boarding house

One of the most appealing aspects of this book is the fact that the first half is set in the early 1990s, which might as well have been a century ago in terms of the way we use technology now. A clunky computer is used for data entry, but they use cards to write up word definitions and keep boxes and boxes of them in a storeroom. Majime lives in a rundown boarding house, where the landlady has retreated to the second floor so that Majime and his books can take over the whole first floor. There are no gleaming white surfaces, no stainless steel, no screens anywhere in this book, and the film based on the book is faithful to this (you can watch a trailer for the film with English subtitles here, and a longer trailer without subtitles here). This is a sepia-tinted world of dusty books and wood (on Kishibe’s first day in the department, her heels catch on the old floor boards and she sneezes constantly). The book ends in the early 2000s, but for the most part Matsumoto, Araki and Majime stick to their old methods. They are intensely curious about new words and usages, but only so they can capture them in their dictionary.

I have read this book three times since it was first published in 2011, and have often wondered why it appeals to me so much (although it’s not just me—it won the 2012 Booksellers Award). We are all intrinsically drawn to fairy tales and legends, and there are certainly echoes here of the holy grail, the ugly duckling, and the pursuit of a seemingly unattainable princess. But I think that most of the appeal for me comes from the idea of a small department working with utter concentration and conviction for almost twenty years on a grand project. When my days are interrupted by breaking news stories flashing across my cellphone screen and the hours are broken down into neat blocks of time in my planner, a life in which you can miss the last train to keep researching a word seems like the ultimate luxury.

I have read this book three times since it was first published in 2011, and have often wondered why it appeals to me so much (although it’s not just me—it won the 2012 Booksellers Award). We are all intrinsically drawn to fairy tales and legends, and there are certainly echoes here of the holy grail, the ugly duckling, and the pursuit of a seemingly unattainable princess. But I think that most of the appeal for me comes from the idea of a small department working with utter concentration and conviction for almost twenty years on a grand project. When my days are interrupted by breaking news stories flashing across my cellphone screen and the hours are broken down into neat blocks of time in my planner, a life in which you can miss the last train to keep researching a word seems like the ultimate luxury.

Recent Comments