Atsuhiro Yoshida is the perfect author when you’re looking for an escape from the everyday that still keeps your brain working. His world is recognizably ours, but skewed just enough that it catches you off guard. Reading Yoshida’s books allows me to take on his whimsical, eccentric way of seeing things for a little while.

「おやすみ、東京」(Goodnight, Tokyo; not available in English translation) is Yoshida’s paean to nights in one of the world’s largest cities, and the most population dense. This allows him to give free rein to his imagination and yet remain in the realm of plausibility: surely if there really is a city in which you can find a peanut crusher and arrange a proper interment for an old phone at 3am, it would have to be Tokyo.

The book is set between about 1am and 4:30am over a series of nights. When the book begins, Mitsuki (the first in a large cast of characters) is at work at 1am in a warehouse that could easily fit two airplanes, but that in this case is full of shelves and drawers crammed with everything a film director could want on his set. The walls are covered with clocks, tapestries and calendars. Mitsuki sees it as a “box of time,” a place in which the past 300 years has been preserved in the shape of this detritus. And yet tonight, the director does not want a trunk from the Taisho era, but a loquat. It’s nearly the end of the season for this fruit, and she only has a few hours in which to locate it. Luckily, Mitsuki has an accomplice in her nighttime searches—Matsui, a taxi driver who works the night shift. Matsui’s driving around the city has given him an intimate knowledge of the city, and he often helps her with her searches. But in the end, it’s not Matsui who helps her find the loquat, but her boyfriend, who has become an amateur scholar of crows during his newspaper route (we’re in Yoshida’s world, after all) and knows of a loquat tree that is a particular favorite with crows.

And it is up in this tree that Mitsuki finds the “loquat thief,” a young woman all dressed in black whom Mitsuki at first mistakes for a very large crow herself. This is Kanako, who collects loquat every year to make wine, carrying on the tradition of her brother even after he disappeared from their apartment one day. She also works at night, answering phones for a support hotline. The people who call don’t necessarily have problems, but just want someone to talk to or just want to be heard. To Kanako, this is completely normal (and in fact,she is a former caller)—wouldn’t anyone who found herself alone in a room at night want someone to talk to?

Yoshida weaves his large cast of characters (also alone at night, sometimes looking for someone to talk to) in and out of his stories. There’s the young woman who collects old phones for disposal at any time of the day or night, the four women who run a shokudo (casual restaurant) that is open all night, a former bartender who now works with Mitsuki and still makes unforgettable coke high balls, and a man who runs a secondhand store that is only open at night because he has day and night mixed up. Then there is Shuro, the “great detective” who, after a day spent going back and forth across Tokyo to visit all of the 19 places he has lived in, takes Matsui’s taxi to a small cinema to watch a film in which his father had a bit part. All of Yoshida’s characters are looking for someone—Shuro is looking for glimpses of his father in old films, Kanako is searching for her brother, Matsui still yearns after a woman who rode in his taxi once, Ayano wonders what has happened to the man who used to come to her shokudo and order ham and eggs, and of course Mitsuki looks for something different every night. All of these characters eventually overlap in some way,but with Yoshida, you can’t expect a pat ending with the characters neatly paired off and reunited. That’s not his way—he seems to respect the solitude of his creations.

All the tropes and themes that crop up so often in Yoshida’s books are here—the shokudo at a crossroads, magicians, movie theaters and obscure films, the search for something or someone, and people who live small lives and find contentment in small (and sometimes slightly weird) things. 「金曜日の本」(Friday’s Books), a snapshot of Yoshida’s childhood, gave me a sense of where these stories may have come from.

Some of his vignettes could have come straight from his fiction. He writes of his family life as an only child with 20 aunts and uncles and innumerable cousins. He tells of buying a bag of senbei on the way back from the sento (public bathhouse) and sharing them with an old monkey kept in a cage in someone’s yard. And of course he writes about books and libraries.

After school, I always played dodgeball in the schoolyard with wild abandon. One day, in the middle of the game, I up and left, and without even being aware of what I was doing, I snuck into the school building, and from there into the lonely library. The air changed at once. I was drawn to the words running along the spines of the books ranged on the shelves. I sensed that the books were in the midst of an ongoing conversation in quiet voices almost impossible to hear. So this was why libraries are always so quiet…

The library he went to was always quiet and dimly lit, built in a forest on the edge of a park. Even as a child, he understood the importance of going to the library alone. He would make his weekly trip on Saturdays, when it always seemed to be raining. Lest we find his description too charming and picturesque, he mentions that one day he saw a dead man hanging from a tree in these woods. It reminded him of a scene from Edogawa Ranpo’s The Boy Detectives Club. The poverty that was so rampant after WWII still had a hold on his neighborhood (Yoshida was born in 1962). The war lingered in other ways as well. Barracks built up around Shimokitazawa Station housed strange stores selling goods that couldn’t be found anywhere else, and still had the feel of the black markets that sprang up after WWII.

Growing up, Yoshida was happiest in libraries, book stores and stationery stores: “There is nothing like the quiet excitement I felt when I bought a folding knife to sharpen pencils, when I bought my first mechanical pencil, or when I picked up a special adhesive called ‘Cemedine concrement.’” Maybe his love of books was a genetic inheritance from his father, much in the way that eye color or dimples in the cheek are passed down. During the war, Yoshida’s father and his family had evacuated to Ichikawa in Chiba, where they rented a room in a small used bookstore. At night, the owner would close up the shop and go home, but Yoshida’s father had free rein and read everything in the shop. Yoshida said that what he read “became his blood and muscle.”

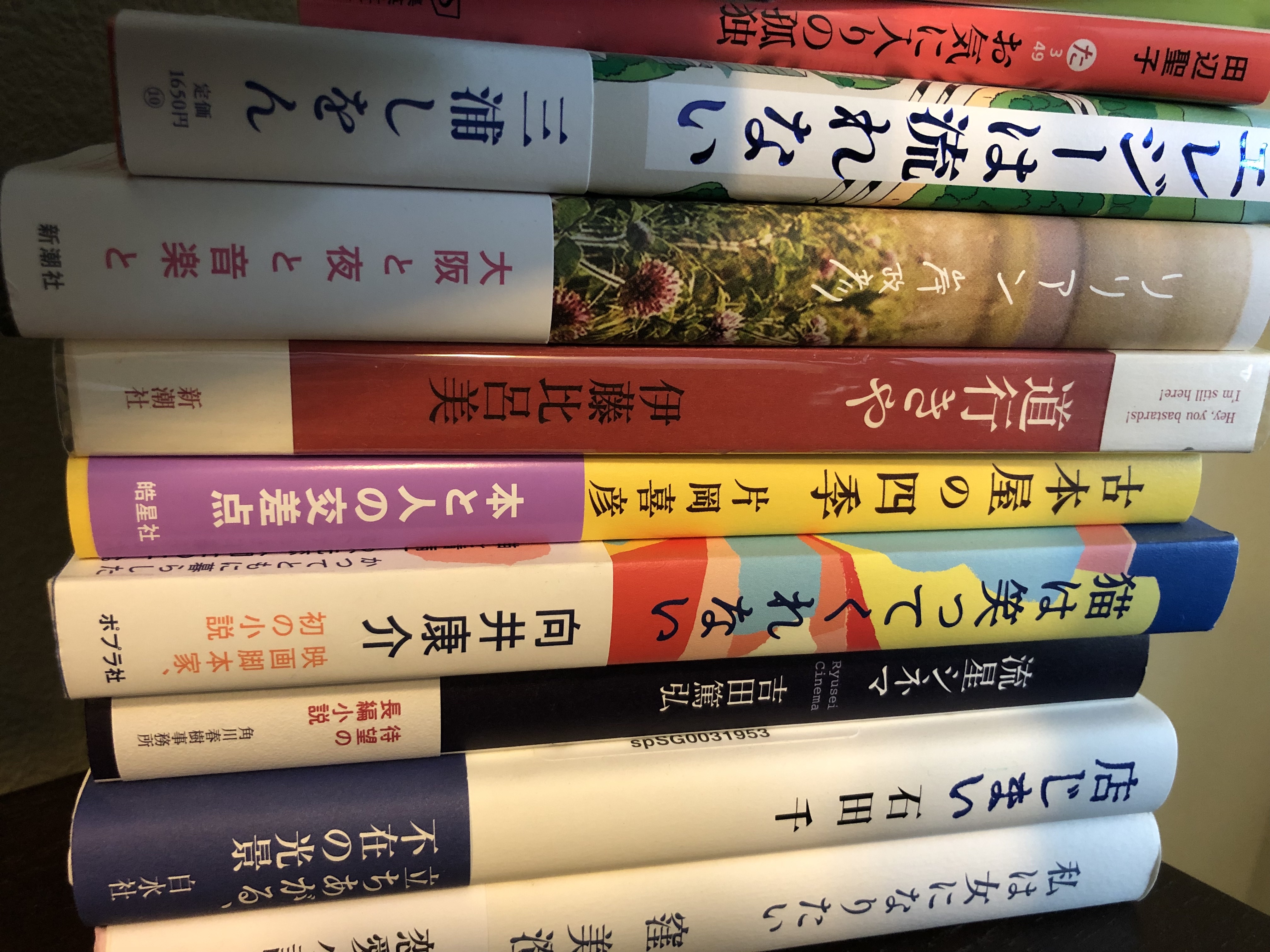

I wasn’t ready to leave Yoshida’s company yet, so I went on to「雲と鉛筆」, a short novel that is long on philosophizing and short on plot (a good combination when Yoshida is the author). By this point, Yoshida had piloted me safely past the midterm elections here in the US, but to soften my entry back into the “real”world, I began reading a volume of his short stories called 「台所のラジオ」. This would be a good entry point for anyone new to Yoshida as these 12 short stories have everything I love about his writing. The radio makes an appearance in every story, but this is the old-fashioned analog radio with a dial, not radio streamed from a mobile phone. Food is the prompt for the characters’ memories and actions here—thinly-sliced fried pork, nori maki, beefsteak, coffee and ochazuke. A paragraph in the story 「油揚げと架空旅行」 (Deep-fried tofu and imaginary travel) sums up the feel of this book (and Yoshida’s writing in general):

I was listening to the radio, in the kitchen. I don’t watch television, nor do I have the bad habit of tying up my acquaintances in long telephone conversations. My one entertainment is the radio, and whenever possible I prefer to listen peacefully to a female announcer with a quiet voice. The perfect program is aired in the evening. A woman with a quiet voice talks about the small things, not the big things, of the world. But the content is not what matters. I am listening to the sound of her voice, not what she is saying.

This is also a good description of Yoshida’s writing: it is not so much the stories he tells, but the atmosphere he creates and the feelings he evokes. In 「金曜日の本」, Yoshida writes that a friend asked him one day what kind of books he read, and at first he said he’d read anything, but when pressed, he realized that the common thread running through the books he’d read was that they “warmed” him. This is what Yoshida’s books do for me.

*I reviewed Yoshida’s book about a female radio announcer (and an eccentric department store clerk) here.

Recent Comments