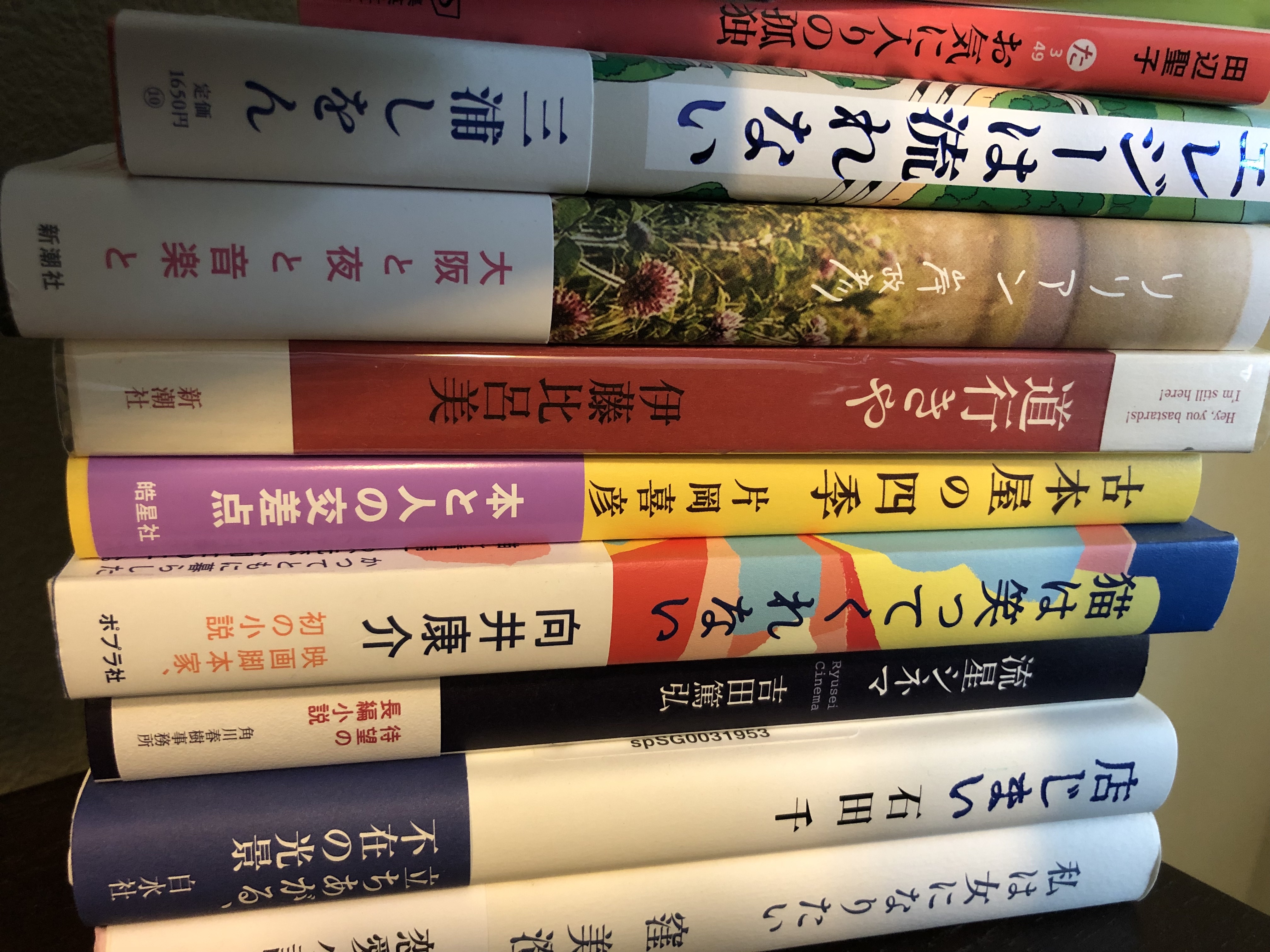

地球星人, 村田沙耶香, 新潮社, 2018

Earthlings, by Sayaka Murata, Shinchosha, 2018

*Since this post was written, the English translation has been published as Earthlings, translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori.

This was a hard book to read, dealing as it does with emotional abuse, incest, pedophilia, sexual abuse, and even cannibalism (would you care for some chunks of human meat in your miso soup? or perhaps simmered with daikon leaves?).

The first half of the book tells the story of Natsuki’s childhood. She believes that she is a witch with powers given her by her stuffed animal, Pyuto. Sensing that the earth is in danger, he came from the star Pohapipinpobopia (that never got any easier to read smoothly) to train Natsuki as a witch so that she can protect the earth.

Her cousin Yu believes he is an alien come from another planet—his mother certainly tells him often enough that she doesn’t know where he could have come from. They meet every summer for the Obon holiday in Akishina, where their large extended family gathers. Natsuki’s grandparents live in a farmhouse where the family had raised silkworms for several generations. The silkworms lived on the upper floors of the farmhouse, and when they became moths, they were allowed to fly around the house. During these summer visits, Natsuki’s uncles pile up rocks to dam a small river and make a swimming hole for the cousins, they play in the rice paddies, eat watermelon, and welcome the ancestors back at the start of Obon with fire (mukae-bi) and send them off again at the end of Obon (okuri-bi). These scenes were warm and really effective in creating a sense of nostalgia, even if it is just borrowed. The warmth of her grandparents and aunts and uncles makes it that much harder to read about the emotional abuse and neglect Natsuki experiences at home.

It is perhaps this abuse and constant denigration that explains why Natsuki sees the world as a factory. In her eyes, the neighborhood she lives in is a warren of burrows for humans. The children will one day be shipped from the factory, where they will be trained so that they can bring food back to their own nests and produce children. Natsuki also sees herself as the family garbage can—when her parents’ and sister’s pent-up anger explodes, Natsuki takes the brunt of it.

Part 2 ends with a bang, when Natsuki is still a child, and quietly takes up the story again when she is 34. Instead of fantasizing about Pyuto and earthling factories, we get a string of quotidian details about the mineral water she has bought, her husband watering their house plants, and the unseasonably warm weather for November. But Murata dispelled my concern that Natsuki had just become another cog in the factory a few pages later. Both Natsuki and her husband have refused to be brainwashed, but they know they will only be allowed to stay in the factory if they pretend they are properly functioning parts. They had found each other on a site out of the public eye for people looking for partners and help with marriage, debt, and suicide. To escape their parents, they married in name only but live separate lives. Natsuki’s husband loves to hear stories about Akishina. It’s when they go together to visit and meet up with Yu again that the story really turns grotesque. Frankly, it felt like a betrayal when Murata tore down the almost idyllic picture of Natsuki’s family home by turning it into the setting for a horror show.

Due to the dark nature of this book and the difficulty in keeping my gag reflex in check, especially in the last 40 pages of this book, I had to read lighter books in tandem for relief. One of these was 偽姉妹 (Fake Sisters), the latest novel by Nao-cola Yamazaki (山崎ナオコーラ). Like Murata, Yamazaki is looking at social problems (in this case, an aging society and smaller families) and trying to find a solution to them, but she does so with a light touch. Three sisters live in a house that is essentially all roof, with impractical touches such as a spiral staircase and few doors. Masako, the middle sister, built it with lottery winnings, but when her marriage (amicably) dissolved and she had a baby, her sisters moved in.

The novel is really an exploration of what happens when Masako decides that she’d rather live with her two friends and make them her sisters. She realized, once her sisters had moved out and her friends had moved in, that she had felt pressure to like her blood relatives and be liked in turn. She wanted to live with a family she had chosen herself. She had named her son after Yukio Mishima, but she hopes that he will feel so free in his life that he will be able to toss off his origins and choose a new meaning for his name. In the epilogue set about 40 years later, people are able to enter into family contracts with other people to share assets, help each other through sickness and grow old together.

The main characters in Earthlings seemed to descend into mental illness, in contrast to Murata’s novel, Convenience Store Woman, in which Keiko has a way of looking at the world that reflects back to us a clear, undistorted look at the social norms that most of us take for granted. The sisters in Pretend Sisters, both real and chosen, were also a welcome contrast with their frank and honest relationships and eagerness to change the parts of society they don’t like. By the end of Earthlings, there was no one for me to sympathize with, which dulled whatever message Murata was trying to get across.

To get a full idea of Sayaka Murata’s range, read this blog post on Brain on Books about her collection of short stories, 殺人出産 (Satsujin Shussan).

コンビニ人間

コンビニ人間

Recent Comments